Barnard 33 & NGC 2024 - The Horsehead and Flame Nebula - 6 hours in HaLRGB

Date: December 17, 2025

Cosgrove’s Cosmos Catalog ➤#0157

Anchored on the leftmost star forming the Belt on Orion, the famous Horsehead and Flame Nebula was a secondary target caught late at night back in October (Click image for hi-res version via AstroBin.com)

Where Dust Meets Fire: B33 and NGC 2024 in Orion

Introduction

This is another secondary target captured late at night during my October capture session. Once my primary target had been set, I caught a few hours on this target - one I normally have a hard time capturing, as past November, we were in a sea of clouds!

I have shot this target before, but I have never captured the vertical striations that can be seen in the curtain of bright nebula that can be seen behind the Horsehead.

For this effort, I took a longer chunk of my integration time dedicated to Ha narrowband capture, where those details can most likely be found.

🔭 Project Summary

Target: B33 – The Horsehead Nebula (with NGC 2024 – The Flame Nebula)

Capture Dates: October 27 & 28, 2025

Constellation: Orion • Distance: ≈ 1,300–1,500 light-years

Type: Dark Nebula (B33) silhouetted against emission backdrop (IC 434) + Emission Nebula / H II Region (NGC 2024)

Imaging Period: October 27–28, 2025 • Total Integration: 5 h 59 m 30 s (LRGB + Ha)

Filters: L · R · G · B (ZWO 36mm Unmounted LRGB Gen II) + Ha (Astronomik 36mm 6 nm)

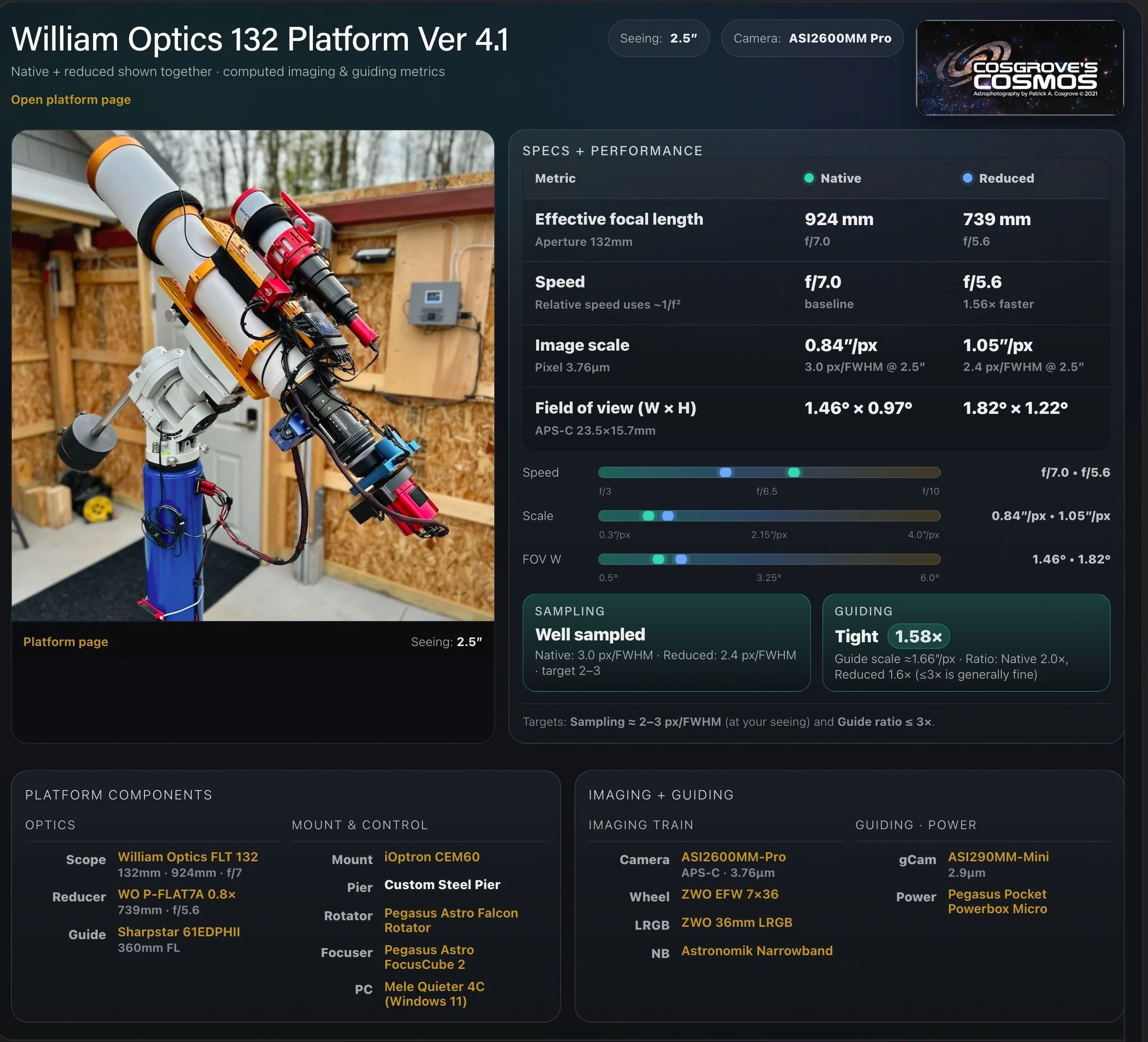

Telescope: William Optics FLT 132mm f/7 APO Refractor + P-FLAT7A 0.8× Reducer

Camera: ZWO ASI2600MM-Pro (−15 °C; Gain 0 LRGB, Gain 100 Ha)

Mount: iOptron CEM60 on custom steel pier

Processing: PixInsight & Photoshop

Location: Whispering Skies Observatory · Honeoye Falls, NY (USA)

Field Includes: IC 431, IC 432, IC 435, LBN 934, LBN 944, LBN 958, LBN 962

The WO 132 f/5.5 Platform, with an iOpron CEM 60 mount, and a ZWO ASI2600MM-Pro camera.

📸 Capture Details

Nights: October 27 & 28, 2025

Number of frames shown is after bad or questionable frames were culled.

| Channel / Filter | Frames × Exposure | Settings | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| L — ZWO Lum (36mm) | 18 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 0 | 27 m |

| R — ZWO Red (36mm) | 35 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 0 | 52 m 30 s |

| G — ZWO Green (36mm) | 35 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 0 | 52 m 30 s |

| B — ZWO Blue (36mm) | 35 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 0 | 52 m 30 s |

| Ha — Astronomik 6 nm (36mm) | 35 × 300 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 100 | 2 h 55 m |

| Total Integration: 5 h 59 m 30 s (LRGB + Ha) | |||

Calibration Frames

- 30 × darks @ 90 s, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 0

- 30 × darks @ 300 s, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 100

- 30 × dark-flats @ each flat exposure time, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 0 or Gain 100 as needed

- Flats: 15 each — L, Ha, R, G, B

Table of Contents Show (Click on lines to navigate)

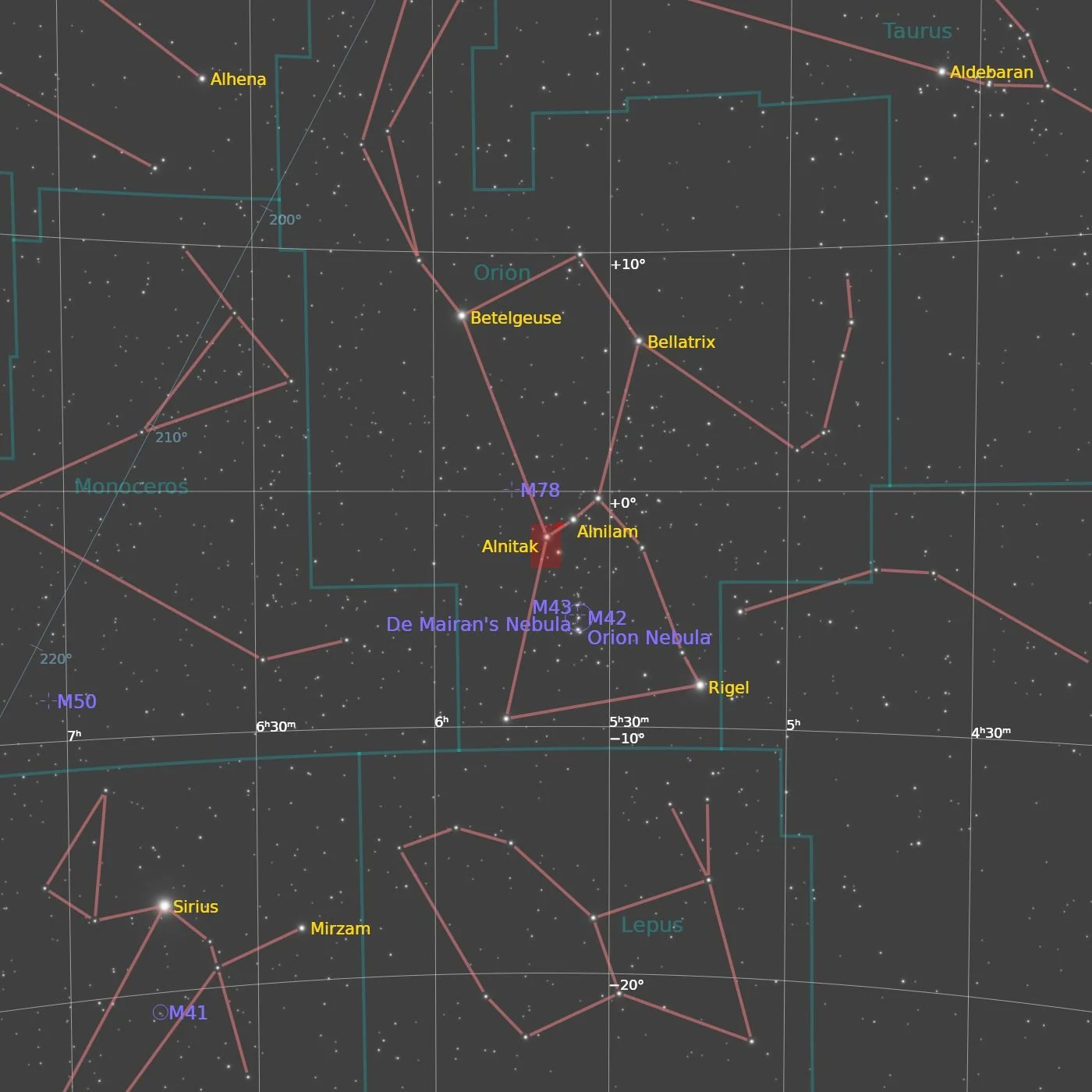

Annotated Image

This annotated image was created with the ImageSolver and FinderChart scripts in PixInsight.

The Location in the Sky

This annotated image created with ImageSolver and FinderChart Scripts in PixInsight.

🔭 About The Target

Overview

The Horsehead and Flame region is anchored by the dark nebula B33 (Barnard 33), a dense foreground dust cloud whose familiar silhouette is seen against the bright hydrogen emission of IC 434. Nearby is the Flame Nebula, NGC 2024 (also cataloged as Sh2-277), an active star-forming emission nebula crossed by prominent dust lanes.

This entire scene sits in the constellation Orion, immediately south of Orion’s Belt star Alnitak, along the western edge of the Orion B molecular cloud; the Horsehead itself is commonly associated with the larger dark cloud complex LDN 1630. Distances reported for this part of Orion vary by technique and reference, but a practical working value is roughly 1,300–1,500 light-years from Earth, placing it in our local spiral-arm neighborhood where fine structure can be resolved with modest amateur equipment given sufficient integration time.

History

The Flame Nebula was first recorded in astronomy during the great era of visual surveys: William Herschel cataloged it in the late 18th century while surveying nebular objects in Orion.

The Horsehead’s discovery story is different because its signature shape is a contrast feature that photography reveals far more readily than the eye; it was identified on photographic plates in 1888 by Williamina Fleming as part of Harvard’s pioneering plate-based sky work. I

n the early 20th century, E. E. Barnard helped establish the modern interpretation by treating it as obscuring material—real dust and gas with structure—rather than a “hole” in the glow, and it has carried the Barnard designation ever since.

Williamina Fleming, credited with the 1888 photographic-plate discovery of the Horsehead Nebula

Portion of Plate b2312 showing the discovery image of the Horsehead Nebula in the collection. Taken on February 7, 1888 from Cambridge with the 8-inch Bache Doublet, Voigtlander

Science

This field is a compact laboratory for understanding how massive stars reshape their birth environments.

The sharp boundary where the glow behind the Horsehead meets the cold dust of the cloud is a classic photon-dominated (photodissociation) interface: ultraviolet radiation heats and chemically stratifies the cloud surface, producing measurable gradients that have been extensively studied using molecular spectroscopy at millimeter- and infrared-wavelengths.

The Flame Nebula, in contrast, is a luminous window into embedded star formation; much of its young cluster is heavily obscured in visible light, so infrared and X-ray observations are used to inventory newborn stars, probe their accretion and outflows, and measure how many retain disks in a harsh, irradiated environment. Together, these targets connect the “sculpting” physics at a cloud edge with the hidden, ongoing formation of stars deeper inside the same complex.

Notable Features in this Frame

What makes the Horsehead and Flame pairing so compelling is that it mixes stark geometry with subtle structure: the Horsehead’s silhouette is unforgiving of over-processing (it is easy to crush the dust into a flat cutout). At the same time, the Flame rewards careful highlight control to preserve its branching dust lanes and layered glow.

This broader framing also adds valuable context by including additional cataloged nebular and dust features—IC 431, IC 432, IC 435, and the Lynds dark-nebula entries LBN 934, LBN 944, LBN 958, and LBN 962—reinforcing that these headline objects are simply the most dramatic knots in a much larger, textured landscape of gas and dust. For observers, it is also a reminder that this region spans a huge dynamic range: visually, it can be challenging under light pollution, but with imaging, it becomes one of the clearest demonstrations of how dust, emission, and starlight interact on parsec scales.

About the Project

Selection and Planning

This is my second Orion target from my last capture session in late October.

I found that my primary targets were set somewhere between 2:30 and 3:30 am. You have to love those long, cool nights in October! The primary targets were done for the night, and I still had a few more hours before sunrise!

I noticed that Orion was up by then.

Orion is absolutely my favorite constellation. When I was a kid, I spent many a cold winter’s night out with my 2.4” Sears Refractor - seeing Orion standing tall in the sky with his belt and sword was a favorite target. One I do not get to shoot very often because of our weather. It seems like November comes along and brings with it a stubborn and seemingly endless cloud deck! I seldom have the opportunity to shoot Orion in the winter here.

So, here was my chance. I likely won't get much integration time, but beggars can’t be choosers! I would get what time on target I could!

The first target I chose was M42. I have already shared that project:

I used my wide-field FRA400 platform for that effort.

My next choice was the region around Alnitak, including Barnard 33 (The HorseHead Nebula) and NGC 2024 (The Flame Nebula). I have shot that before (I’ll discuss it in the next section), but I wanted to revisit it.

Why?

Well, it’s been a while since I shot it last. I now have faster scopes, better cameras, more powerful processing tools, and greater processing experience.

I wanted to see what I could do with where I am now. Also, the last time I photographed this, I hoped to capture the shimmering vertical striations visible in the nebula behind the Horsehead. In that shot, you could see hints of it. But I really wanted to bring it out this time around if I could.

Previous Efforts

As it turns out, the first time I photographed this region is not documented on my website.

It was well over 30 years ago, and I was shooting gas-hypered Kodak Tech Pan film. I gas-hypered the film myself and then loaded it into an OM-1 camera attached to a Meade wide-field 622 scope.

I had no telescope drive in those days, but I was able to mount this on a friend's massive fork-mounted 16-inch Newtonian scope.

This was Rick Albrecht’s scope. If you have read my posts, then you have heard this name several times. Rick had a wonderful 16” scope, mounted on a massive steel fork mount with an 18” bronze drive gear. It was situated in a domed observatory on a hill. Rick had built everything himself - down to cutting the teeth on the drive gear, grinding the optics, welding the mount, you name it - he did it! I was fortunate enough to mount my little scope on his beast of a scope and go along for the ride. In fact, I think this is the only image that ever really came out back when I was trying to shoot with Gas-haypered film.

Here is the image itself - forgive the reflection on it - I just shot it with my iPhone while it was still in the frame!

Perhaps I should update my image gallery with this image being shown as my first!

Taken some 33 years ago on Gas-Hypered Techpan 2415 film, OM-1 Camera body, Meade 633 Rih Field scope, and piggy back ride on Rick Albrecht’s wonderful 16-inch fork-mounted netwonin telescope.

Then came a 30-year gap in my interest in astronomy. Once I was back in the game, I started trying to shoot targets in Orion whenever I had a chance.

My first effort was in February of 2020. I shot 90 minutes with a one-shot camera on my William’s Optics 132mm f/7 FLT. This can be seen here:

My First Barnard 33 Shot - Feb 2020

My second effort was in December of 2021. This was a 4-hour and 40-minute integration using the same scope, but with my first mono camera - the ASI1600MM-Pro. This shot turned out well, and you could see hints of the vertical stational pattern I was interested in capturing. However, the bright star Alnitak produced numerous microlens artifacts with that camera, which greatly complicated my image processing. You can see the Project here:

My Second Barndard 33 Shot - Dec 2021

Below are all three versions so you can compare them.

Comparison of the 2020, 2021, and 2025 efforts

Capture Strategy

I decided to capture this on my William Optics 132mm FLT, same as the first two. But this time I will be using the flattener and 0.8X reducer, which took it from f/7 down to f/5.5. It now sports a next-generation ASI2600MM-Pro camera, so I don’t expect any microlensing artifacts.

I would be shooting primarily in LRGB with 90-second exposures, a gain of 0, and a cooler temperature of -15 °C.

But I would also be going heavy with 300-second Ha narrowband exposures to try and get the vertical striation patterns I wanted. This would also have a lower temperature of -15 °C, but a camera gain of 100 to compensate for the reduced narrowband signal.

Data Capture

Data capture was done on the nights of October 27 and 28, 2025. On the first night, I captured only Ha, R, G, and B subs. The second night, I captured Ha and LRGB subs.

So why no L subs on the first night?

Operator error - pure and simple. I just messed up the sequence programs! On the second night, I noticed this and corrected it.

Tracking seemed to go well.

Later blink analysis revealed no frames were eliminated due to clouds or other issues. Every frame captured was used!

🧩 Capture Time by Filter

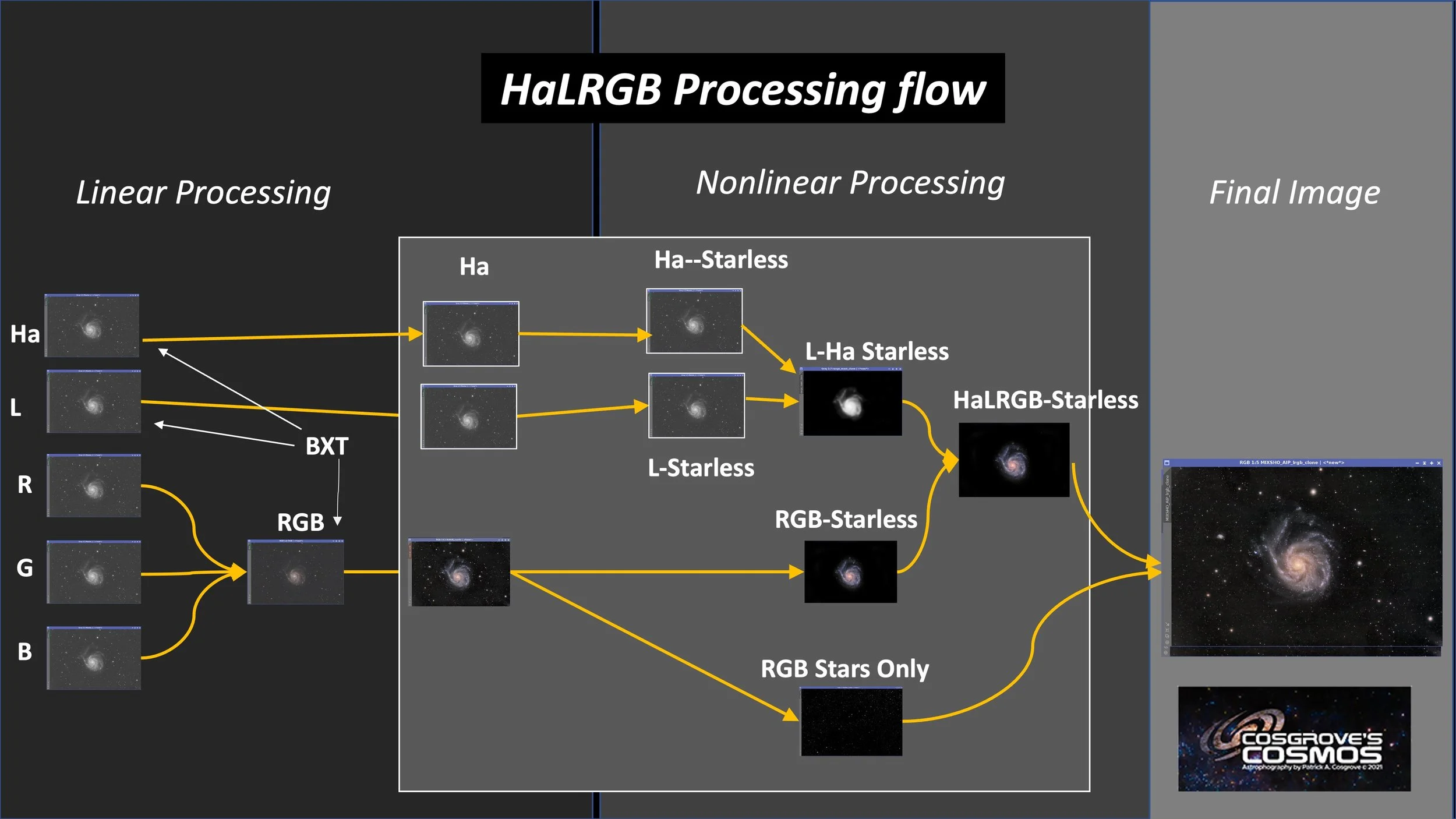

Processing Overview

The processing for this project fits my high-level processing workflow for the HaLRGB image as seen below.

My typical HaLRGB Starless Workflow.

I did all of my linear processing the on the Ha, L, and RGB images and then removed the stars. The starless images went nonlinear and processing was done to enhance each of the images.

A hybrid LHa image was created to use a the the new luminance image. This was interesting because the two images had very different levels of details as can be seen below:

Master Lum vs Ha images

I experimented with different weight schemes but ultimately used a 25-75 weight scheme. When I used this image to insert it into the RGB image, I encountered a problem: the resulting image was too light, and the reds turned a pale pink.

The LHa signal was so strong relative to the RGB image that I needed to back up and use LinFit to calibrate the RGB image to the LHa signal level. After doing this, I had pretty good results.

Normally, at this point, I would add the stars back in and then move to Photoshop to do the final polishing.

However, I noticed that some polishing operations could hurt stars if they were in the region being tweaked. I have begun adjusting my workflows to accommodate this.

Before adding the stars back in, I saved the starless RGB image as a 16-bit unsigned TIFF, imported it into Photoshop, and then made additional polishing changes. The image is then exported again into PixInsight, and the stars are re-added This acts to better protect the stars.

Detailed and Annotated Image Processing Walkthrough

Typically, I conclude one of these imaging projects by documenting the processing steps I used on this image. But this section can make the overall post very large and, at times, slow to load.

I am now creating a secondary, standalone page to hold this information. You can access this page by clicking the link below. Returning to this page is as simple as clicking the back arrow in your browser or selecting a different menu option at the top of the page.

I hope you like this new format!

Hit the Link below to see the detailed image processing walkthrough page for this Imaging Project!

Final Results

I am pleased with the final results!

Given the low integration times, I was able to pull much more detail out of the shimmering “curtain” behind the Horsehead nebula. I am no longer having to deal with microlensing artifacts with this new camera. The bright stars are still bloated and have some flare, but that is hard to avoid.

I am also pretty happy with the framing.

With the 0.8X reducer, the field of view is wider, allowing me to include IC 432, seen on the far left. It also includes some amazing Ha pillars in the upper-left quadrant, which are often missing from some compositions.

One thing I was concerned with at first was the structure visible in IC 432 and other small nebulae in the field. At first, I thought this was a lens or processing artifact, but after looking at other Astrobin images with a wider field of view, I realized these were actual features of the nebula and should, in fact, be there!

More Information

🔭 Target Details

SIMBAD: Barnard 33 (Horsehead Nebula) – The canonical object record with identifiers, coordinates, and references for B33.

Aladin Lite: Barnard 33 field – Interactive sky atlas view centered on B33 with survey overlays and catalog layers.

NASA Hubble: The Horsehead Nebula – Hubble’s overview of B33 silhouetted against IC 434, with context on dust, illumination, and structure.

NASA Hubble: Swirls of Dust in the Flame Nebula – Hubble’s wide-field look at NGC 2024, with distance, location in Orion, and star-forming context.

ESA: Euclid’s view of the Horsehead Nebula – A detailed, wide Euclid view of B33 and surrounding Orion dust lanes.

📜 History & Naming

Harvard Plate Stacks: Variable Stars and Nebula (Williamina Fleming) – Highlights Fleming’s work and the early photographic discovery context for the Horsehead.

Harvard/CfA Wolbach Library: Williamina Fleming – A concise biography that explicitly credits Fleming’s 1888 identification of the Horsehead on Harvard plates.

NOIRLab Image: The Horsehead Nebula – Observatory-grade outreach page with naming, identification, and discovery context for B33 in IC 434.

ESA Herschel: A Horsehead, a Flame and hidden gems in Orion B – Historical notes on NGC 2024 (Herschel-era discovery) plus Orion B context from a major mission team.

NASA PDF: “A Horse of a Different Color” – Hubble outreach sheet that summarizes the Horsehead’s recorded history and why it stands out in modern imaging.

🔬 Science & Observations

A&A: The IRAM-30m line survey of the Horsehead PDR – Peer-reviewed deep spectroscopy of the Horsehead’s photon-dominated region (PDR), linking chemistry to the UV-illuminated edge.

NASA Hubble: Flame Nebula proplyds and disk erosion – Explains Hubble’s search for protoplanetary disks in NGC 2024 and what intense radiation may do to planet formation.

NASA Webb: Horsehead (Euclid, Hubble and Webb images) – Multi-mission comparison that shows how wavelength and resolution change what you can learn about B33 and its surroundings.

NASA Webb: Flame Nebula (Hubble and Webb observations) – Infrared vs. optical views of NGC 2024, useful for understanding what’s hidden by dust and what’s revealed in IR.

Caltech/IPAC 2MASS: Picture of the Week (NGC 2024) – Infrared context for the Flame region, with distance framing and links into the broader Orion Molecular Cloud complex.

💡 Interesting Facts & Outreach

APOD (2025-12-10): The Horsehead Nebula – Outreach-friendly explanation of why B33 is visible at all (silhouette against IC 434) and why it’s a favorite imaging target.

ESA/Webb Image: Horsehead (Euclid, Hubble and Webb) – A clean comparison set that’s excellent for explaining what different telescopes “see” in the same region.

ESA Image: Flame Nebula in visible and infrared light – A striking outreach comparison showing how dust obscuration changes dramatically between optical and infrared views of NGC 2024.

Astronomy Magazine: The Horsehead Nebula in Orion—an observing guide – Practical observing/imaging perspective and sky context that pairs well with an astrophotography project page.

AstroBin: Horsehead Nebula search results – A curated, community-driven reference set for B33 images, useful for comparison of framing, filters, and integration strategies.

Platform used for this project

Software

Capture Software: PHD2 Guider, NINA

Image Processing: Pixinsight, Photoshop - assisted by Coffee, extensive processing indecision and second-guessing, editor regret, and much swearing…..