Messier 42/43 – The Great Orion Nebula - 6.35 hours in HaLRGB

Date: December 8, 2025

Cosgrove’s Cosmos Catalog ➤#0156

A wide-field view of the Orion Nebula region. The red glow of the Great Orion Nebula (Messier 42, right) and the blue Running Man Nebula (NGC 1977, upper left) shine in the constellation Orion’s “Sword.” This vibrant cloud complex lies well within our Milky Way, about 1,300–1,500 light-years from Earth. (Click image for hi-res version via AstroBin.com.)

The Sword of Orion, Forged in Starlight!

Awarded Flickr Explore Status!

Introduction

Messier 42/43 is one of the true Gems of the Sky and probably one of the most photographed objects in Astronomy. Why choose this target? Hasn’t it been done to death?

I rarely get to shoot targets in Orion due to our winter weather. So when I had the opportunity, I had to go for it!

I should warn you that this image may be a bit over the top! My goal here was to bring out the structure, detail, and color of this target.

Maybe this will make this stand out from the thousands and thousands of other shots of this target.

Maybe you will like seeing the detail and color.

Maybe you will hate it for being overdone.

Either way - I have had a lot of fun shooting and processing this amazing target!

🔭 Project Summary

Target: Messier 42 / Messier 43 – The Great Orion Nebula Region (with the Running Man Nebula)

Capture Dates: October 27 & 28, 2025

Constellation: Orion • Distance: ≈ 1,300–1,500 light-years

Type: Emission Nebula + H II Region (M42/M43) with nearby Reflection Nebula (Running Man / NGC 1977)

Imaging Period: October 27–28, 2025 • Total Integration: 6 h 21 m 30 s (LRGB + Ha)

Filters: L · R · G · B (ZWO 1.25-inch LRGB Gen II) + Ha (Astronomik 1.25-inch 6 nm)

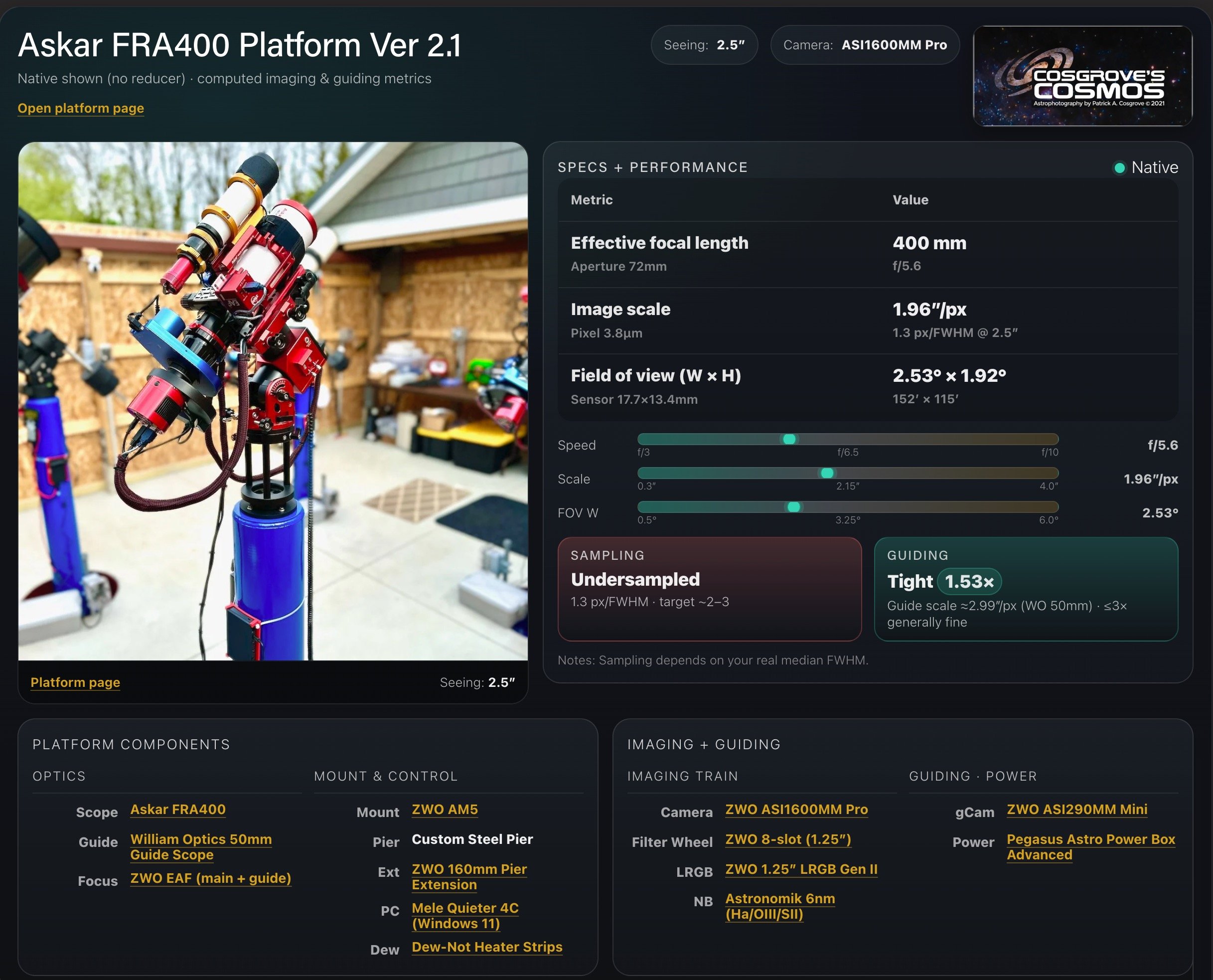

Telescope: Askar FRA400 widefield astrograph (≈400 mm)

Camera: ZWO ASI1600MM-Pro (−15 °C; Gain 139 LRGB, Gain 139 Ha)

Mount: ZWO AM5 on custom steel pier

Processing: PixInsight & Photoshop

Location: Whispering Skies Observatory · Honeoye Falls, NY (USA)

The Askar FRA400 Platform, with an ZWO AM5 mount, and a ZWO ASI1600MM-Pro camera.

📸 Capture Details

Nights: October 27 & 28, 2025

Number of frames shown is after bad or questionable frames were culled.

| Channel / Filter | Frames × Exposure | Settings | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| L — ZWO Lum (1.25-inch) | 30 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 45 m |

| R — ZWO Red (1,25-inch) | 29 × 30 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 14 m 30 s |

| G — ZWO Green (1.25-inch) | 30 × 30 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 15 m |

| B — ZWO Blue (1.25-inch) | 31 × 30 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 15 m 30 s |

| R — ZWO Red (1.25-inch) | 31 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 46 m 30 s |

| G — ZWO Green (1.25-inch) | 31 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 46 m 30 s |

| B — ZWO Blue (1.25-inch) | 29 × 90 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 43 m 30 s |

| Ha — Astronomik 6 nm (1.25-inch) | 31 × 300 s | bin 1×1 • −15 °C • Gain 139 | 2 h 35 m |

| Total Integration: 6 h 21 m 30 s (LRGB + Ha) | |||

Calibration Frames

- 30 × darks @ 90 s, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 0

- 30 × darks @ 30 s, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 0

- 30 × darks @ 300 s, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 100

- 30 × dark-flats @ each flat exposure time, bin 1×1, −15 °C, Gain 0 or Gain 100 as needed

- Flats: 15 each — L, Ha, R, G, B

Table of Contents Show (Click on lines to navigate)

Annotated Image

This annotated image was created with the ImageSolver and FinderChart scripts in PixInsight.

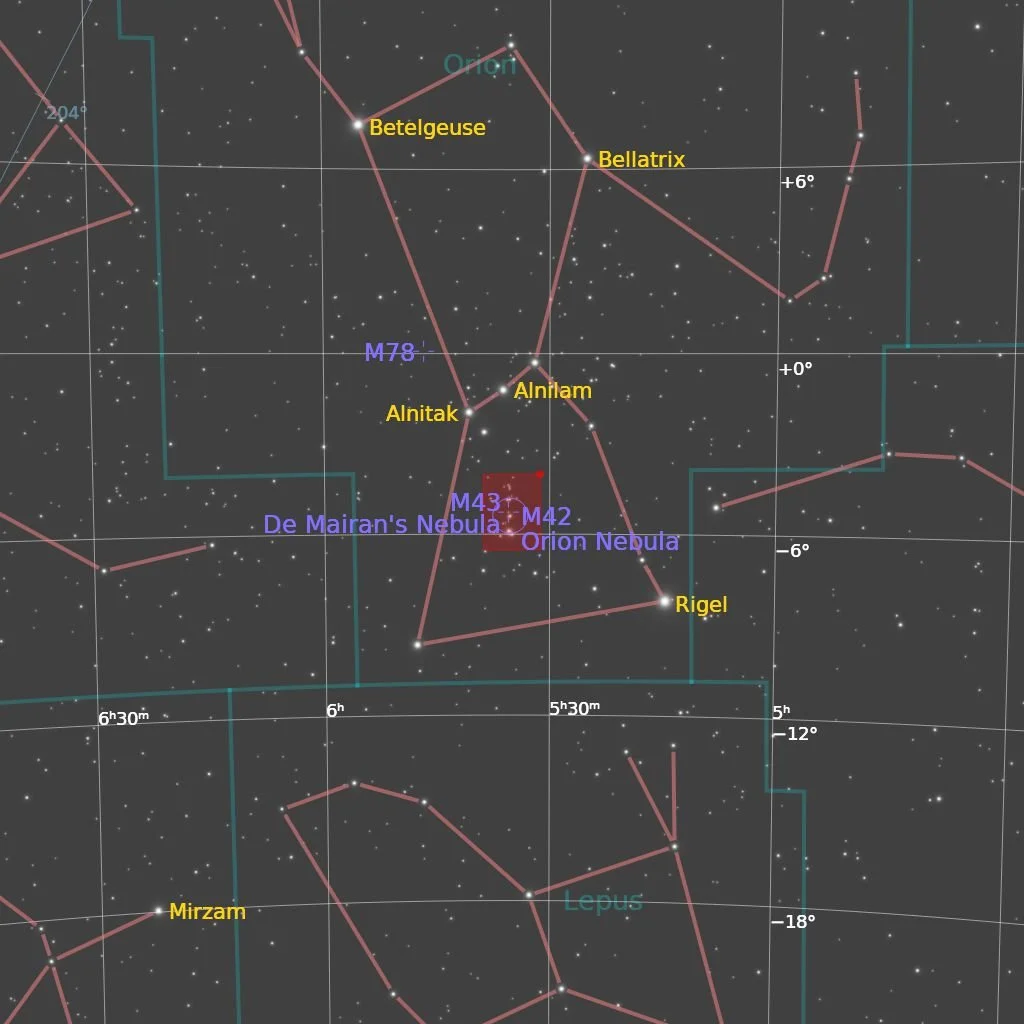

The Location in the Sky

This annotated image created with ImageSolver and FinderChart Scripts in PixInsight.

🔭 About The Target

Overview

The Orion Nebula region is one of the brightest and most picturesque areas of the night sky, located in the sword of Orion the Hunter.

The centerpiece is Messier 42 (M42), also known as the Great Orion Nebula, a colossal diffuse nebula spanning roughly 25 light-years in diameter. This is a stellar nursery – a giant cloud of gas and dust where new stars are actively being born. In fact, M42 contains about 2,000–3,000 times the mass of the Sun in raw material for star formation. At an estimated distance of around 1,300–1,350 light-years (with some sources putting it at around 1,500 light-years), the Orion Nebula is the closest large star-forming region to Earth.

Despite its great distance, this nebula is visible to the naked eye on a dark night – appearing as a faint fuzzy “star” in Orion’s sword. In photographs and telescopic views, M42 reveals a brilliant reddish glow from ionized hydrogen gas illuminated by hot young stars at its core.

With the Orion Nebula’s glowing folds lie several distinctive features. A dark bay of obscuring dust, poetically nicknamed the “Fish’s Mouth,” splits the bright nebula. This dust lane actually separates M42 from its smaller companion nebula, Messier 43 (M43).

M43, also called De Mairan’s Nebula, is a semi-detached portion of the Orion Nebula’s cloud, forming its own H II region (ionized hydrogen region) just north of the Fish’s Mouth. Appearing as a comma-shaped patch of faint haze, M43 is fueled by a massive young star (NU Orionis) at its center, which makes the gas cloud glow. Though less prominent than M42, M43 is part of the same overall cloud complex and lies at a similar distance (about 1,300–1,600 light-years). It was first noted by the French astronomer Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan in the 18th century (hence its name) and later catalogued by Charles Messier.

Just a bit further north in Orion’s sword is the Running Man Nebula, a separate but nearby formation that often accompanies M42/M43 in wide-field images. The Running Man Nebula is a reflection nebula – meaning it shines primarily by reflecting the light of stars rather than emitting its own glow.

It is commonly associated with the designation NGC 1977 (part of a larger nebula complex, Sharpless 279) and lies roughly 1,500 light-years from Earth in the same neighborhood of Orion.

In photographs, the wispy blue glow of the Running Man Nebula surrounds a young star cluster, and dark dust lanes cutting through it create the uncanny shape of a human figure in motion – giving rise to its popular nickname. While the Orion Nebula (M42) is dominated by reddish-pink hydrogen emission, the Running Man Nebula (NGC 1977) has a bluish hue, caused by starlight scattering off fine interstellar dust.

Together, M42, M43, and NGC 1977 form a stunning tableau of cosmic creation, all part of the vast Orion Molecular Cloud Complex – a massive star-forming network that also includes nearby famous nebulae like the Horsehead Nebula and Barnard’s Loop.

History & Discovery

The Orion Nebula has captivated observers for centuries and holds an important place in the history of astronomy.

The first recorded observation of its nebulous nature was made in 1610 by the French astronomer Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, who pointed his early telescope at the middle “star” of Orion’s sword and realized it was not a star at all, but a fuzzy cloud. This was among the earliest discoveries of a deep-sky nebula.

A year later, in 1611, Jesuit astronomer Johann Cysat also noted the cloud. Interestingly, the famed astronomer Galileo Galilei observed the Orion sword region around 1617 – he sketched some of the bright young stars now known as the Trapezium Cluster – but he failed to notice the surrounding nebula, likely because his telescope’s narrow field of view and high magnification made the diffuse glow hard to see.

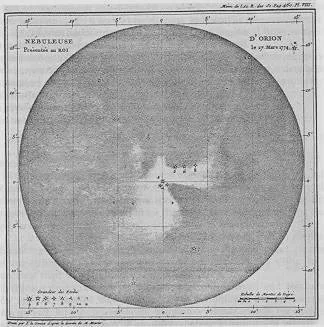

The Orion Nebula was next studied by Christiaan Huygens, who, in 1656, made one of the first detailed drawings of its bright central region (now sometimes called the Huygens Region in his honor). Over the ensuing decades, other astronomers took note: Edmond Halley published an account of the nebula in 1716, and French scientist Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan described the neighboring M43 nebula by 1731.

Messier's drawing of the Orion Nebula in his 1771 memoir, Mémoires de l'Académie Royale.

By the mid-18th century, the Orion Nebula’s fame was spreading.

It earned a spot in Charles Messier’s catalog of comet-like objects – Messier observed and cataloged it as “Messier 42” (M42) on March 4, 1769. He also cataloged the small adjacent patch as Messier 43, acknowledging de Mairan’s earlier discovery. In 1786, astronomer William Herschel turned his larger telescopes to this region and discovered the fainter reflection nebula above M42, later known as NGC 1977 (the core of the Running Man Nebula). Herschel noted a hazy glow around the star 42 Orionis, not realizing he was seeing a separate nebula. (The distinctive “running man” shape itself wasn’t recognized until modern astrophotography revealed it in detail.) Herschel’s son John Herschel would go on to catalog the nearby star cluster NGC 1981 in 1827, completing the inventory of this rich region.

The Orion Nebula also became a milestone in astrophotography and spectroscopy.

In 1880, American physician and amateur astronomer Henry Draper succeeded in taking the very first photograph of a nebula – an image of M42. His pioneering 50-minute exposure (and a longer one in 1881) was black-and-white and grainy, but it marked the dawn of a new era: the capture of the cosmos on camera.

Around the same time, astronomers began using spectroscopy to unravel nebulae’s secrets. In 1864, William Huggins dispersed the light from the Orion Nebula and found that it did not show a continuous star-like spectrum but rather a few bright emission lines. This demonstrated that M42 is composed of glowing gas rather than a cluster of unresolved stars and revealed specific elements (such as hydrogen) in the nebula. Huggins’ work was revolutionary – it showed that the Orion Nebula and others like it are truly gaseous “stellar nurseries,” confirming what telescopic observers like William Herschel had suspected. Since then, the Orion Nebula has remained one of the most studied objects in the sky. It has been sketched, photographed, and observed in every wavelength, continually inspiring scientists and stargazers alike. Even ancient cultures paid attention to this celestial cloud – for example, the Maya of Mesoamerica saw the Orion Nebula’s glow as the “cosmic fire of creation” in their mythology.

Draper’s First image of M42 in 1881

Another Draper image of M42 from 1882

Scientific Significance

Beyond its sheer beauty, the Orion Nebula region has been an invaluable natural laboratory for science, teaching us much about how stars and planetary systems form.

Modern telescopes have peered into M42 and found it teeming with newborn stars and developing solar systems. At the heart of the Orion Nebula lies the Trapezium Cluster, a group of extremely young, hot stars that formed from the nebula’s gas. To the eye through a small telescope, four bright stars in a trapezoid pattern stand out, but in reality, the cluster contains dozens of stars, including several massive ones.

These stars blast the surrounding cloud with intense ultraviolet radiation, which ionizes hydrogen gas and makes the nebula glow brightly. The Trapezium’s energetic light and stellar winds have literally carved out a cavity in the center of M42, pushing gas aside and creating a window that allows us to peer deep into the nebula’s core. This harsh environment might seem destructive, but it’s actually revealing many wonders: embedded in the Orion Nebula, astronomers have discovered hundreds of protoplanetary disks, or “proplyds” – disks of dust and gas around young stars that are the early stages of planetary systems. In fact, about 180 proplyds have been detected in Orion, more than anywhere else, making it a rich source for studying the formation of new solar systems. Some of these disks have even been directly imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope, appearing as tiny dark silhouettes or glowing frisbee-like structures around infant stars. Through Orion, we learned that planets likely form in these disks while their host stars are still in their infancy.

Hubble Telescope Shot of M42 (Credit:

NASA, ESA, M. Robberto ( Space Telescope Science Institute/ESA) and the Hubble Space Telescope Orion Treasury Project Team)

The Orion Nebula has also provided insight into different types of young stars.

Scientists have observed numerous Herbig–Haro objects – energetic jets of gas shooting out from newborn stars at high speed that collide with surrounding material and produce bright shock fronts. These cosmic jets and outflows, seen in Orion, help us understand how young stars shed angular momentum and interact with their environment.

Additionally, surveys of the Orion Nebula Cluster (the larger grouping of about 2,000 stars that includes the Trapezium) have identified many brown dwarfs – “failed” stars not massive enough to sustain hydrogen fusion – lurking in the mix. Intriguingly, astronomers even found dozens of free-floating objects with planetary masses in Orion. In the late 1990s, Hubble observations uncovered about 13 drifting gas-giant planets (also called rogue planets or sub-brown dwarfs) wandering within the nebula without a parent star. These strange objects, roughly the mass of Jupiter, likely formed in the collapsing gas cloud alongside the stars but were later ejected from nascent star systems, teaching us that not all planets remain bound to their stars.

Nor is M42 the only part of this region fostering cosmic discoveries – the neighboring Running Man Nebula has yielded surprises too.

Although it is a reflection nebula (lit by starlight from young stars like 42 Orionis), it turns out that star formation is happening there as well. Hubble Space Telescope observations in 2012 revealed at least one proplyd (protoplanetary disk) within NGC 1977, complete with a bent jet from its central protostar, similar to those in M42. Subsequent studies identified six more proplyds in the Running Man Nebula (plus one spotted by the Spitzer infrared telescope), all clustered near the star 42 Orionis. This was a groundbreaking find – it marked the first time astronomers observed proplyds being photoevaporated by a B-type star (42 Ori) rather than the usual O-type stars in the Orion Nebula. It shows that even slightly less massive stars can significantly influence their surroundings. In 2021, researchers announced Hubble’s discovery of a spectacular 2-light-year-long jet emanating from a newborn star (cataloged as Parengo 2042) in NGC 1977. This plasma jet, illuminated by nearby 42 Ori’s radiation, was observed carving through the nebula – a dramatic example of a young star making its presence known. All these findings across M42, M43, and the Running Man Nebula enrich our understanding of the star formation process – from the collapse of clouds into stars, to the formation of protoplanetary disks and jets, and even the early dynamical dance that can fling out rogue planets. In essence, the Orion Nebula region is a cosmic classroom where we’ve learned how stellar nurseries work and how our own Sun and planets might have arisen in a similar nursery billions of years ago.

Interesting Facts

The Orion Nebula region is not only scientifically enlightening but also full of fascinating tidbits that bridge the gap between professional astronomy and amateur stargazing.

M42 is so bright (approximately magnitude 4 overall) that under clear dark skies, you can see it without any telescope – it appears as a faint haze around the middle star of Orion’s sword.

In binoculars or a small telescope, it’s a breathtaking sight: a glowing cloud with a hollowed-out center (the Fish’s Mouth dark gap) and the tiny Trapezium stars sparkling at its heart. Those four primary Trapezium stars, arranged in a trapezoid, are just the tip of an iceberg – they’re among the youngest stars known, only a few million years old, and their energy lights up the nebula like a cosmic night-light. Visually, observers often report a greenish tint in the Orion Nebula when viewing it through a telescope. This is because the human eye is most sensitive to green wavelengths in low light, and one of the nebula’s strongest emission lines happens to be a greenish glow from doubly ionized oxygen (once mysterious, historically referred to as “nebulium”). Long-exposure photographs, however, reveal the nebula’s true colors: predominantly pinks and reds from hydrogen-alpha emission, with hints of purple, blue, and even a faint green core.

The Orion Nebula also holds a few “firsts” in astronomy. As mentioned, it was the first nebula ever photographed – a feat achieved by Henry Draper in 1880. Draper’s pioneering image proved that photography could capture details invisible to the human eye and paved the way for astrophotography as a crucial tool in astronomy. M42 was also among the first nebulae to be spectroscopically analyzed (by William Huggins in 1864), leading to the discovery of nebular emission lines and the realization that we were observing fluorescing interstellar gas. In terms of catalogs and nomenclature, the Orion Nebula carries many labels: Messier 42, NGC 1976, and it’s sometimes even referred to as Sh2-281 in the Sharpless catalog of emission nebulae. M43 is also known as NGC 1982, and the Running Man’s complex includes NGC 1977 (as well as NGC 1973 and 1975 for its fainter parts). Historically, before these catalog numbers, people called M42 the “Great Nebula in Orion”, emphasizing its prominence.

Another fun fact: the Orion Nebula’s apparent size in our sky is enormous – about 1 degree across, or roughly two full Moons side by side! That is the span of the fainter outer nebulosity visible in photographs. Our eyes can’t easily see the full extent, but long exposures reveal billowing clouds that dwarf the Moon's disk. Also, nestled just above the Orion Nebula is the open star cluster NGC 1981, which is visible to the naked eye and actually makes up the northern end of Orion’s sword (though the nebula’s fame often overshadows it). As for the Running Man Nebula, it carries an alternate spooky nickname – the “Ghost Nebula” – because some see the shape as a cartoon ghost with arms raised. (This name can cause confusion, since another unrelated nebula in Cepheus is also called the Ghost Nebula.) Regardless of the moniker, spotting the Running Man visually is challenging; it’s much dimmer than M42, and the “running man” shape is only really evident in photographs. This makes it a favorite challenge for astrophotographers, who love framing it alongside the Orion Nebula in wide-field shots. In fact, the entire Orion Nebula region is often a rite of passage for amateur astronomers and photographers – it’s one of the most imaged and studied objects outside our solar system. Its grandeur and relative closeness mean even modest telescopes can reveal some structure, while big observatories continue to uncover new surprises. From being a cornerstone of Messier’s catalog to a showcase for Hubble’s capabilities, the Orion Nebula and its companions remain a constant source of wonder.

About the Project

Planning

I should start by saying that Orion is my absolute favorite constellation, and the Messier 42 complex is one of my favorite objects.

I remember gazing at this with my early telecopes and being able to see the Tapezium and the “Fish’s Mouth.”

My First Telescope circa 1970 - A Sears and Roebuck 2.4 inch refractor.

Given this, you might think my portfolio includes many images of Orion; however, it does not. I only have a couple of images from Orion - these were taken on the rare cold, clear nights in winter when the ever-present clouds depart for a short period of time.

In Western New York, it seems that from November through March, we have unending clouds. It seems that as soon as the air is colder than the temperature of the Great Lakes, they turn into cloud-producing engines, and my skies shut down.

I have been processing data from a string of targets that I shot over five clear nights in late October. I took advantage of those long nights to get a lot of integration time on my primary targets, but those set in the west by around 2-3 am, and I still had several hours of darkness each night I wanted to use.

At this time of night, Orion was rising, and I realized that this was a perfect opportunity to add in some secondary targets in Orion. So I added a new target to each telescope that would take over once the primary target had set.

M42 was the first one I chose to go after again.

I know, you’re thinking, “Great choice, Pat! Pick the most photographed object in the night sky and spend your limited sky time shooting yet another version of this target. Just what the world needs, yet another image of M42!”

I hear you and had the same thoughts myself.

But this one is kind of special for me.

Decades ago, I would study this visually through the telescope. The first astro image I did, which I was really proud of, was of M42. It was the first image I ever thought was worth sharing with the local astrophoto community.

So this target is an old friend, and I really wanted to visit it once again.

I created my sequence in NINA and was ready to go.

Previous Capture Attempts

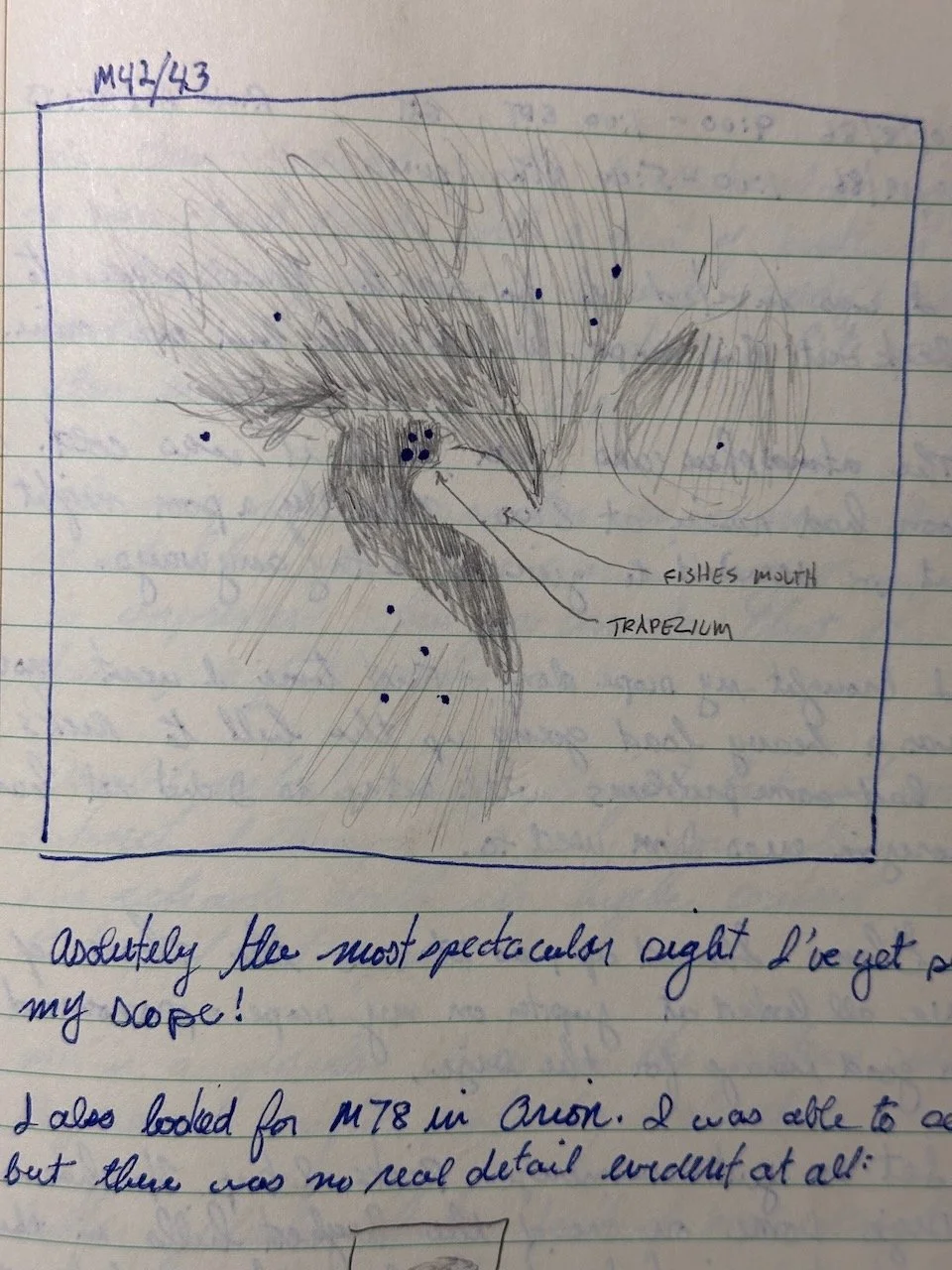

As I said, this is one of my favorite sections of sky. Back in 1987, I was doing almost visual astronomy as I had no tracking drive at the time. So my first way of imagining M42 was by rough sketches. Here is a shot from my observing notebook from November of 1987:

A sketch I made at the telescope in 1987!

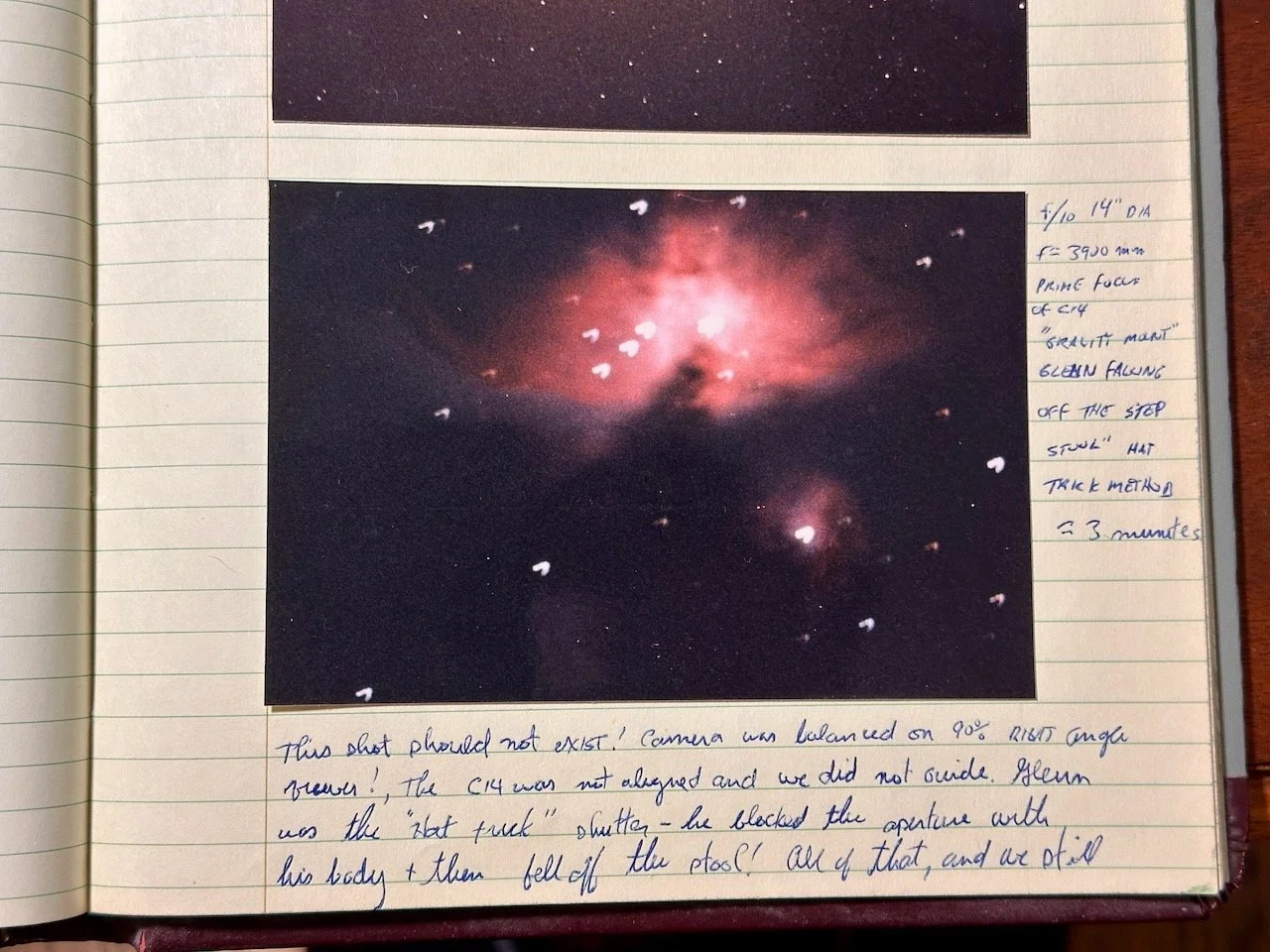

And here is one of my very first attempts at photographing through the telescope.

This was done with my observing partner at the time, Glenn Cummings, and his C14 telescope! We pointed it at M42, then I balanced my camera on its right-angle eyepiece holder. While I did this, Glen stood on a stool and blocked the telescope's front. I opened the camera shutter, and Glenn heroically threw himself off the stool, thus commencing the exposure!

Yes - I know, none of this was a recommended procedure, and I doubt anyone will be using this method anytime soon. But Glenn and I had fun doing it, and I must admit that I laughed out loud as I read the details on this image from my notebook!

My first ever attempt at photographing M42! This was in 1988.

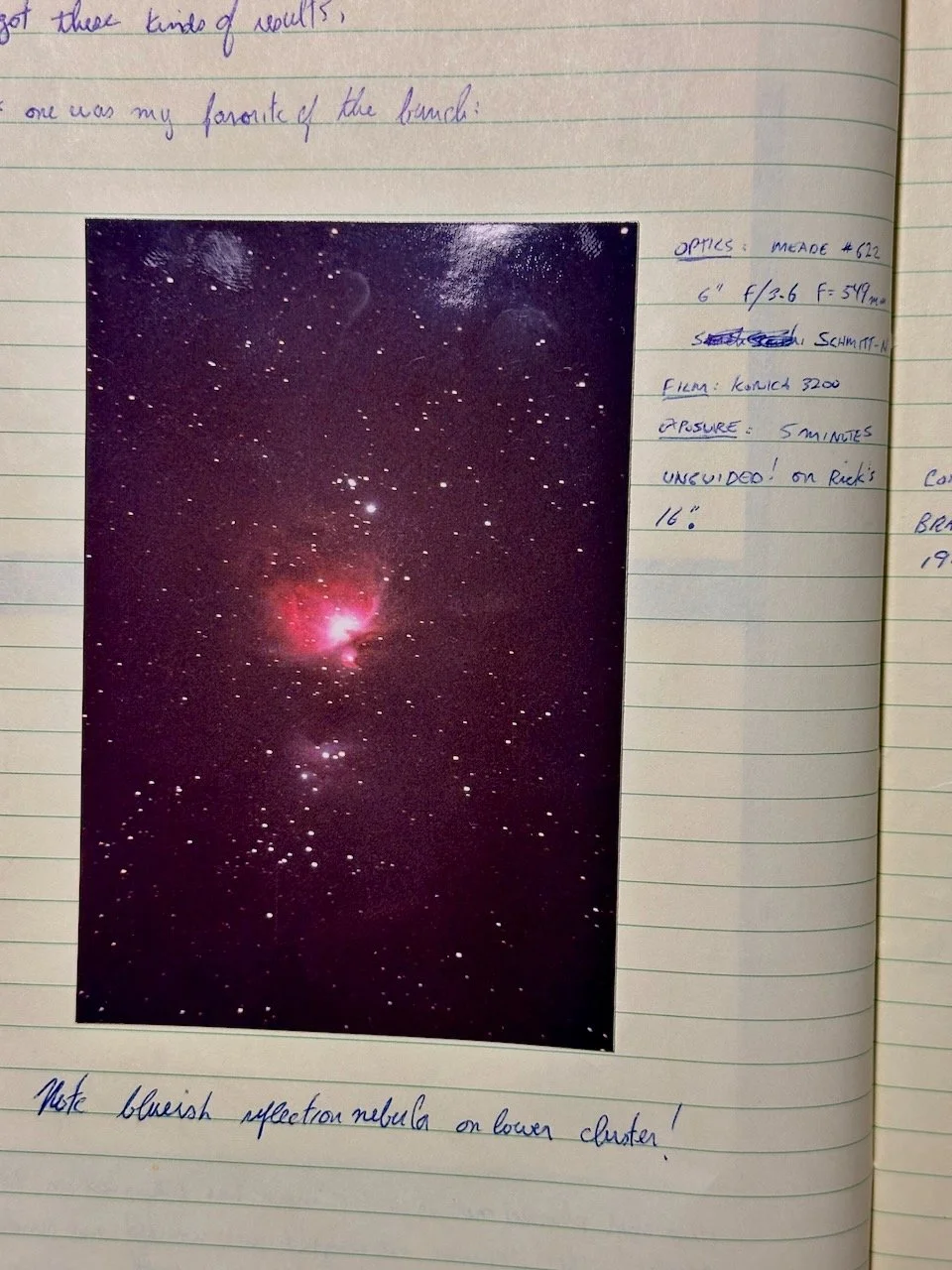

A little later, I got better results by piggybacking my camera and a Meade #622 6-inch rich-field scope on another friend's telescope. This was Rick Albrecht's beautiful 16-inch scope. This produced the following image:

Later that year…. this was piggybacking on a large telescope.

The first time I captured M42 as part of my more recent astrophotographic journey was in December 2019.

This was shot with my first telescope - the Williams Optics 132mm FLT @f/7 using a one-shot color camera and only 1.5 hour integration! You can read about that here:

And here is that image for your convenience:

My first attempt from 2019.

I was very proud of this image, and this image still gets a lot of traffic on my website.

There are several differences between this image and the current one.

This image was taken with a very short integration time

It had no Lum or Ha Data

The short-exposure subs were much shorter at 2 seconds than at 30 seconds used this time around (a mistake on my part).

The image scale was more than 2x the current version.

Capture Strategy

I have to say that I planned all of this quite quickly, and it wasn't as well thought out as some of my other efforts. But here was my thinking:

Shoot some 30-second RGB subs. This would hopefully be a short enough exposure that I could get detail from the super-bright Tapezium section of the nebula.

Shoot some 90-second LRGB subs. This will target the less-bright regions of the nebula.

Shoot some 300-second Ha subs. This will pick up all of the HII in the area.

I set things up so that in each exposure cycle, I shot a single 30-second R, G, and B sub, followed by a 90-second L, R, G, and B sub, and then a single 300-second Ha sub. Then we would cycle back and repeat.

I did not know how many nights I would get, but even a couple would yield longer integrations than I had achieved in the past. By adding short-exposure subs, longer-exposure subs, Lum subs, and narrowband Ha subs, I hoped to create a very detailed image of this famous object.

Data Collection

Data was collected on the nights of October 27 and 28, 2025.

The nights were cold enough that I could set a camera cooling target to -15 degrees C, and I knew the cameras could handle it. I set up the camera with a default gain of 139.

The NINA sequence handled things very well, and my tracking looked consistently good.

Processing Overview

Preprocessing and Post Processing

I did not have a very long integration for this project, but I did have a faster scope (f/5.5 vs f/7) and some Ha narrowband data.

I planned to create 30-second and 90-second master RGB images and combine them with the HDR-Composition tool. This would all be done in linear mode.

Then I would do my linear processing on the L and Ha images, and go nonlinear. At this point, I would combine the Ha and L images to create a hybrid luminance channel. Why do this in the nonlinear domain? I wanted to apply the standard nonlinear processing to each image before combining them.

This would be processed and then folded into the RGB HDR image. Finally, I would use the Ha image to enhance the red channel of the RGB HDR image.

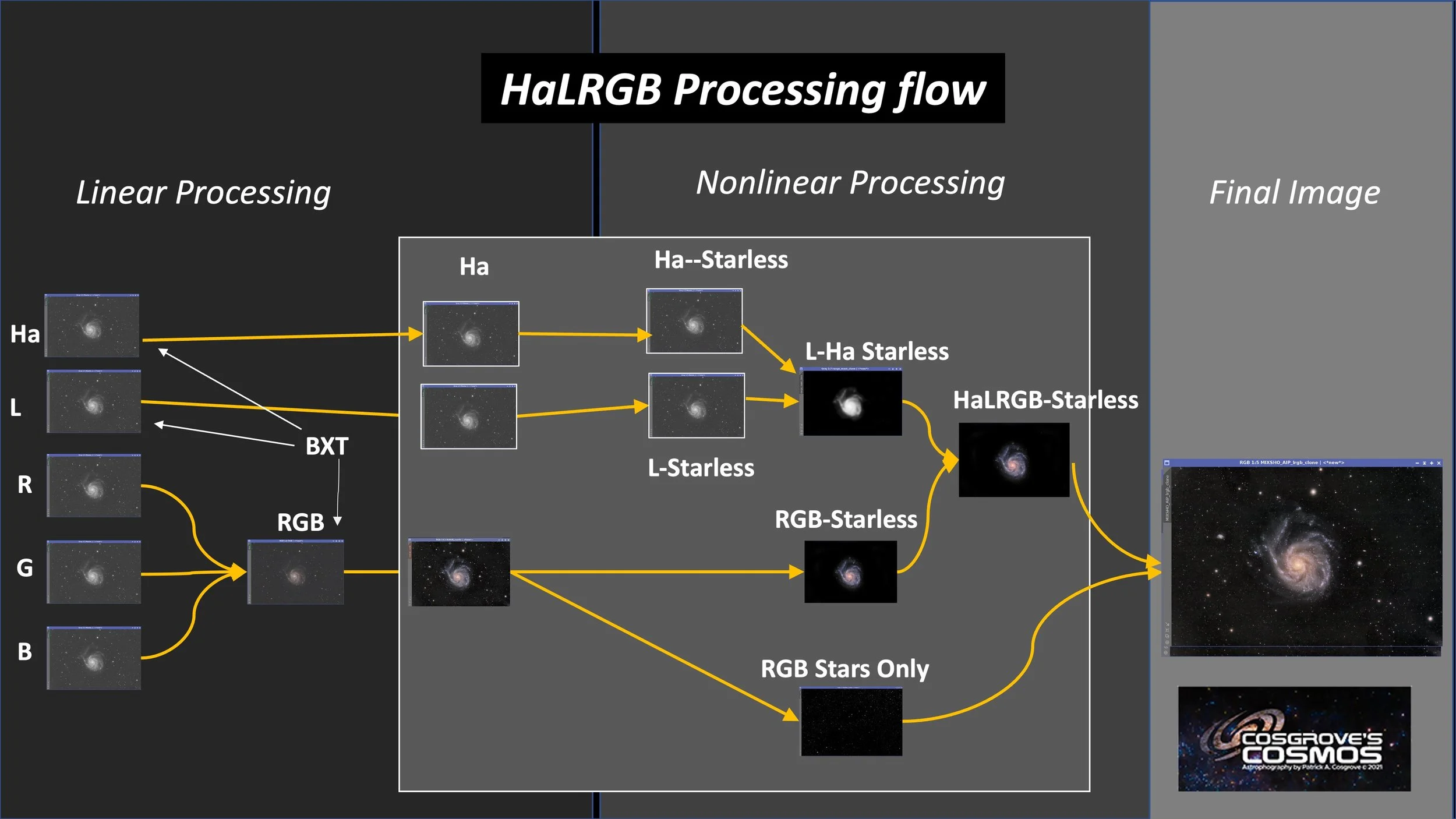

Once the HDR combo image was created, the rest of my processing would loosely follow my HaLRGB Plan.

On the one hand, the processing was straightforward and followed the high-level flow shown below. On the other hand, I was creating many master images and folding them together at just the right time, so this would involve many steps and take a while to complete.

My typical HaLRGB Starless Workflow.

Detailed and Annotated Image Processing Walkthrough

Typically, I conclude one of these imaging projects by documenting the processing steps I used on this image. But this section can make the overall post very large and, at times, slow to load.

I am now creating a secondary, standalone page to hold this information. You can access this page by clicking the link below. Returning to this page is as simple as clicking the back arrow in your browser or selecting a different menu option at the top of the page.

I hope you like this new format!

Hit the Link below to see the detailed image processing walkthrough page for this Imaging Project!

Final Results

My goal here was to show the detail, structure, and color found in this target - and to bring this out as much as possible. I think I achieved that.

But I was also saying that, in doing this, I really pushed the sharpening and local contrast enhancements, and that may have gone too far for some folks. If you are in this camp, no problem, I can respect that.

I am, however, disappointed that I did not resolve the Trapezium very well.

Part of this is due to the short 400mm focal length and the smaller image scale yielded by this astrograph. But the main issue, I feel, is that the short exposure is still way too long. I should have gone with something like 5-second subs. My bad!

More Information

🔭 Target Details:

NASA APOD – The Great Nebula in Orion (2024 Nov 4) – NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day featuring M42, noting it spans ~40 light-years and lies ~1500 light-years from Earth.

SIMBAD – M42 (Orion Nebula) – Astronomical database entry listing M42 as an H II region and giving its coordinates (05:35:16.8, –05:23:15, J2000).

Aladin Lite – Orion Nebula field – Interactive sky atlas view centered on the Orion Nebula, allowing zoom and multi-survey overlay exploration of the region.

Trapezium - Wikipedia entry for the Trapezium

Wikimedia Commons – Orion Nebula – Category page with hundreds of freely-licensed images of M42 (over 600 files as of now).

📜 History & Naming:

Wikipedia – Orion Nebula – Overview of M42’s names and discovery, noting that older texts call it the “Great Nebula in Orion”.

Encyclopedia Britannica – Orion Nebula – Summary of M42’s history, mentioning its discovery by Peiresc in 1610 and that it was the first nebula ever photographed (in 1880)

NASA (Hubble) – Messier 42 (Orion Nebula) – NASA article describing M42’s significance, including its mythic view as a “cosmic fire” by the Maya and its status as the nearest large star-forming region (~1500 ly away) visible to the naked eye.

🔬 Science & Observations:

Chandra (2000) – X-Ray Hot Stars in the Orion Nebula – Chandra X-ray results showing the Orion Nebula Cluster (~2000 young stars within ~10 light-years) and the compact Trapezium subgroup (~0.5 ly radius) of ∼300,000 yr age.

EarthSky – JuMBOs in the Orion Nebula (2023) – Article on James Webb Telescope findings: 540 free-floating planetary-mass objects found in M42 (at 1,344 ly), including puzzling binary “JuMBOs” (Jupiter-mass Binary Objects).

💡 Interesting Facts & Outreach:

Space.com – Orion Nebula: Facts about Earth’s nearest stellar nursery – Popular astronomy article noting that M42 (Messier 42) is the nearest star-forming region; fun facts include that it generates enough water to fill Earth’s oceans ~60 times per day.

APOD (2024 Sep 10) – Horsehead and Orion Nebulas – NASA’s APOD mosaic featuring the dark Horsehead Nebula alongside the glowing Orion Nebula, illustrating both famous nebulae in one wide field.

Chandra Observatory – Images of the Orion Nebula – Chandra photo album showing X-ray and optical views of M42; describes intense X-ray flaring by young stars in the cluster (ages ~1–10 Myr).

Platform used for this project

Software

Capture Software: PHD2 Guider, NINA

Image Processing: Pixinsight, Photoshop - assisted by Coffee, extensive processing indecision and second-guessing, editor regret, and much swearing…..