The Telescopes of Whispering Skies Observatory: Four Platforms, Side by Side

“Why four? One telescope is never enough. Eight is… a problem.”

Updated February 18, 2026

Viewing note

This post is table-heavy. I’ve made it work on smaller screens where possible, but it’s most readable on a full-size PC display.

The tables below are designed to make the trade-offs obvious: image scale, field of view, tolerance, and why each platform earns its spot.

Platform Overview

Table of Contents Show (Click on lines to navigate)

Summary

This page is the “why” behind my four-platform imaging setup. The goal is not variety for its own sake — it’s deliberate coverage across target size, field, and tolerance, while keeping the workflow consistent.

At a high level, the platforms currently form a clean ladder:

FRA400 (400 mm) — wide-field context: big nebula complexes, star fields, and composition-first imaging.

WO132 (739 mm) — general-purpose mid-scale: a dependable nebula and galaxy platform when target size is uncertain.

AP130 (1080 mm) — smaller, brighter targets and “reach” work when I want detail with a refractor look (and when the SCA260 is already committed).

SCA260 (1300 mm) — small targets and tight framing: galaxies, groups, and anything where reach matters and mechanical discipline is non-negotiable.

Two design choices drive everything you’ll see below:

Stable foundations first. The piers are not cosmetic — they are the difference between repeatable performance and chasing variables night after night.

Standardize where it matters. Three platforms are built around the same APS-C mono camera class, so the math, framing, calibration, and processing behavior stay consistent even as focal length changes.

Introduction

In May 2025, my Whispering Skies Observatory became operational. The exterior wasn’t fully complete, but enough was in place to make sense to install the rigs and start capturing data again.

At first, I brought over the three telescopes I had been using from the driveway. The observatory was built with a fourth pier, and before long, I made a deliberate choice for what belonged there — and the system became what it is today.

Each platform has its own detailed post, but this article is the missing piece: how the four work together, where each one wins, and why the differences are intentional. If you’re here for the quick version, jump straight to the platform links below—then come back for the deeper comparisons.

History

My first telescope was the William Optics 132mm FLT APO. It was my first scope, and it is still one of my favorites. I used it for a couple of years in its f/7 configuration, then added a flattener/reducer to bring it to its current f/5.6 configuration.

Shortly after that, I had an opportunity to acquire my second telescope: the Astro-Physics 130mm EDT Starfire. That acquisition has its own story (linked here):

The story behind how I got this scope

This was premium optics at a very reasonable price. I didn’t choose the focal length or aperture as part of a top-down plan — the opportunity presented itself, and I jumped on it.

The Askar FRA400 was originally purchased as a portable scope. I didn’t end up using it that way, but it turned out to be a perfect wide-field platform — the one that lets me capture targets that are simply too large to do cleanly with the longer systems.

The Sharpstar SCA 260 V2 was a very conscious choice. I wanted a longer focal length for chasing galaxies, but I also wanted a fast scope. In that sense, the SCA260 V2 is unique. A fast, long focal length astrograph.

The current configuration for each platform is linked next. If you only want the hardware details, start there—then come back for the “why” behind the comparisons.

Corrected reflector for tight framing and small galaxies—built for stiffness and repeatability

Refractor “reach” when I want clean stars, a tighter field, and the SCA260 is already committed.

My dependable mid-scale platform when target size is uncertain—predictable night to night.

Big targets and rich star fields—wins on field size and composition, not raw aperture.

Current State

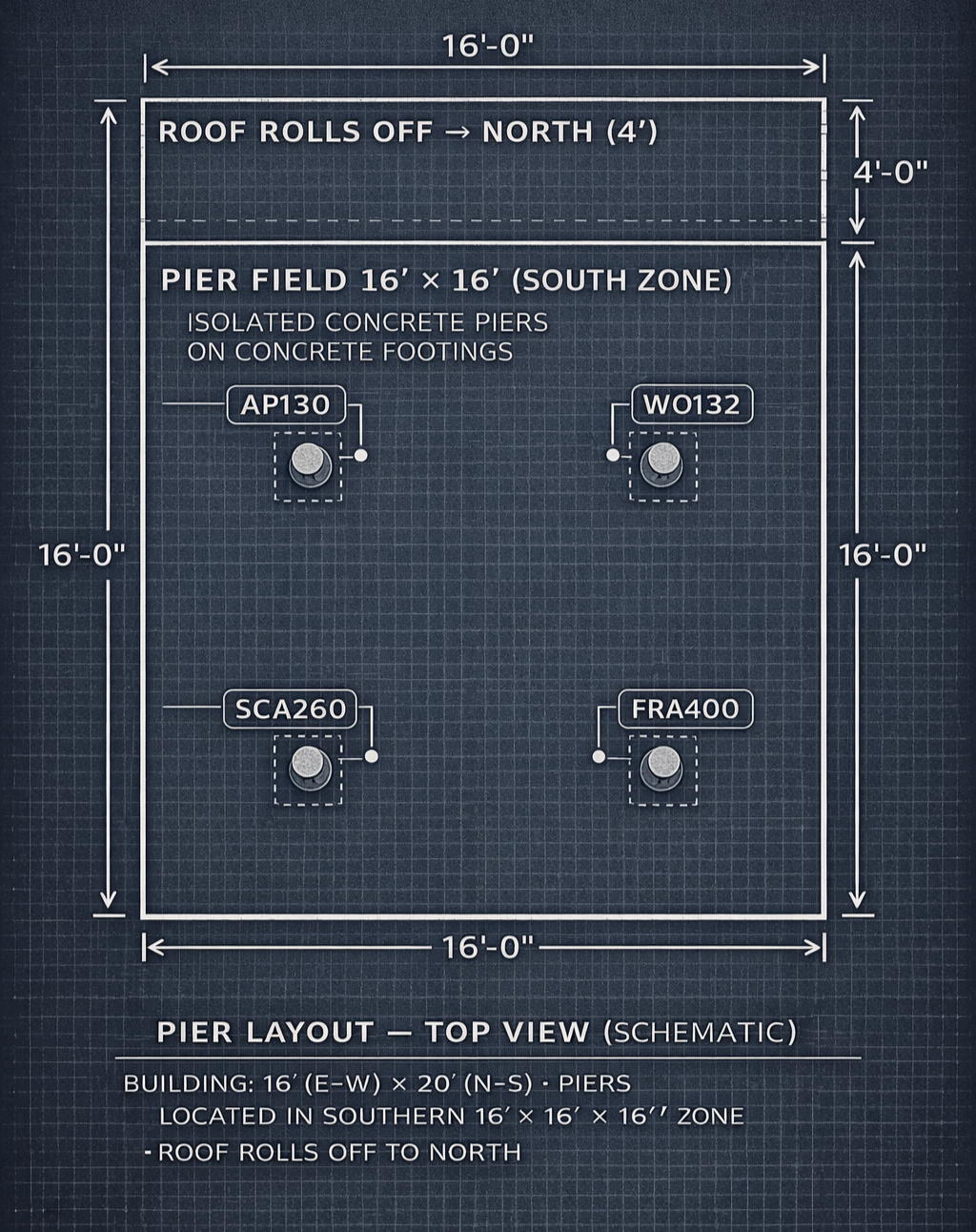

I have four piers in the observatory, which I refer to as the NW, NE, SW, and SE piers.

The southern piers are more limited in how low they can go before a scope runs into trees or the observatory wall. The northern piers have the best access to low targets toward the south.

Pier layout (top view) — Building footprint (16′ × 20′) with the southern 16′ × 16′ pier field and platform assignments; roof rolls off to the north.

SW: SCA260 — I expect higher-elevation work here, so I’m looking through the least atmosphere.

SE: FRA400 — wide-field platform; planned pier extension reduces low-altitude constraints.

NW: AP130 / NE: WO132 — generalist refractors with the best access to low southern targets.

Why I’m not worried about low-north access:

Targets rotate around Polaris — if something is low, I can usually wait until it climbs.

Low northern sky also tends to sit in the Rochester light dome, so it’s rarely where my best work happens anyway.

Looking north inside my Whispering Skies Observatory. All four scopes sitting on their piers!

Mounts (Mechanical Backbone)

Mounts are the mechanical backbone of each platform — they set the ceiling for star shape, repeatability, and how hard you have to work to get a clean integration.

But the mount is only half the story. Every system sits on a heavy-duty custom steel pier, which removes a whole class of problems: tripod flex, settling, seasonal re-leveling, and the “mystery drift” you get when the ground or a tripod leg becomes part of the system.

With the piers in place, the mount is working on a stable foundation, which is exactly what you want when you’re chasing consistent performance night after night.

With the foundation and mount strategy established, the rest of the portfolio analysis is straightforward: I’m going to walk through the key dimensions that actually drive outcomes — optical design, image scale, sensor choice, rotation strategy, and guiding architecture.

With the pier problem essentially solved up front, the differences you see in this table are mostly about matching mount capacity and tracking tolerance to each platform’s focal length and sampling regime.

A Comparison and Analysis of the Four Platforms

Looking at the Capability Now in Place

From here on, I’m treating the four platforms as a single system. Each section looks at one critical dimension — and why that dimension matters more (or less) depending on focal length, sampling, and tolerance.

A) Optical Style and Design Philosophy

First, let’s look at the fundamental optical design of these instruments. These four instruments are not redundant. They are intentionally different optical solutions to different problems.

Optical architecture drives field correction, tolerance to tilt/collimation, and how much “fuss factor” it takes to keep a system delivering.

Askar FRA400

- Flat field by default — widefield is the native behavior

- Composition and “big structure” targets in one frame

- More forgiving than long-FL reflectors when conditions aren’t perfect

William Optics FLT 132

- Classic refractor look: clean stars and predictable behavior

- A strong “daily driver” platform for mixed target selection

- Accessory-driven flexibility (reducers/flatteners as needed)

Astro-Physics AP130

- High-contrast refractor rendering with excellent consistency

- Tight framing with refractor behavior and stable results

- “High confidence” performance session to session

Sharpstar SCA260 V2

- Reach and speed for small galaxies, groups, and tight framing

- Corrected performance when the mechanical/optical chain is dialed in

- Exposure economics refractors can’t match at the same framing

This portfolio is intentionally diverse because optical design is not just an academic detail — it dictates field correction, tolerance to tilt/collimation, and how much “fuss factor” it takes to keep a system delivering.

The FRA400 is the wide-field specialist because the correction is baked into the design. That matters. It means the flat field is the default behavior, not something you bolt on later with a flattener and a stack of adapters. In practice, that translates into fast wide-field composition and big-structure targets — with a workflow that is generally forgiving compared to long-focal-length reflectors. The trade is straightforward: 72mm is not about raw reach. It wins with field size and convenience, not small-target capability.

The WO132 and AP130 are both triplet refractors, but they are not redundant. The WO132 is classic “mid-aperture refractor territory” with accessory-driven flexibility — reducers and flatteners let you tune it to the target class, and when spacing and tilt are handled correctly, it delivers the clean stars and predictable behavior people expect from a good APO. The AP130 is my high-confidence refractor: tight framing with refractor behavior, excellent contrast, and stable performance session to session. Astro-Physics confirmed by serial number that my objective is oil-spaced, and that shows up in the consistent rendering. The cost is speed. It is not “fast,” and in deep sky that matters — you pay for that rendering in exposure economics.

Then there’s the SCA260, which lives in a different world. It’s a corrected reflector built to deliver reach and speed for small galaxies, groups, and tight framing — and it earns its keep exactly there. The flip side is that “good enough” setup practices stop being good enough. Collimation, tilt control, and mechanical rigidity matter most on this platform because the optical design will reveal every weakness upstream. When it’s dialed in, the performance is unmatched in the portfolio at that framing. When it isn’t, the system tells you immediately.

That’s the point of this coverage strategy. These are not four versions of the same idea — they are four fundamentally different approaches that let me choose the right tool based on target size, composition goals, and how much tolerance the night (and my patience) can afford.

B) Aperture (Diameter) and What It Actually Changes

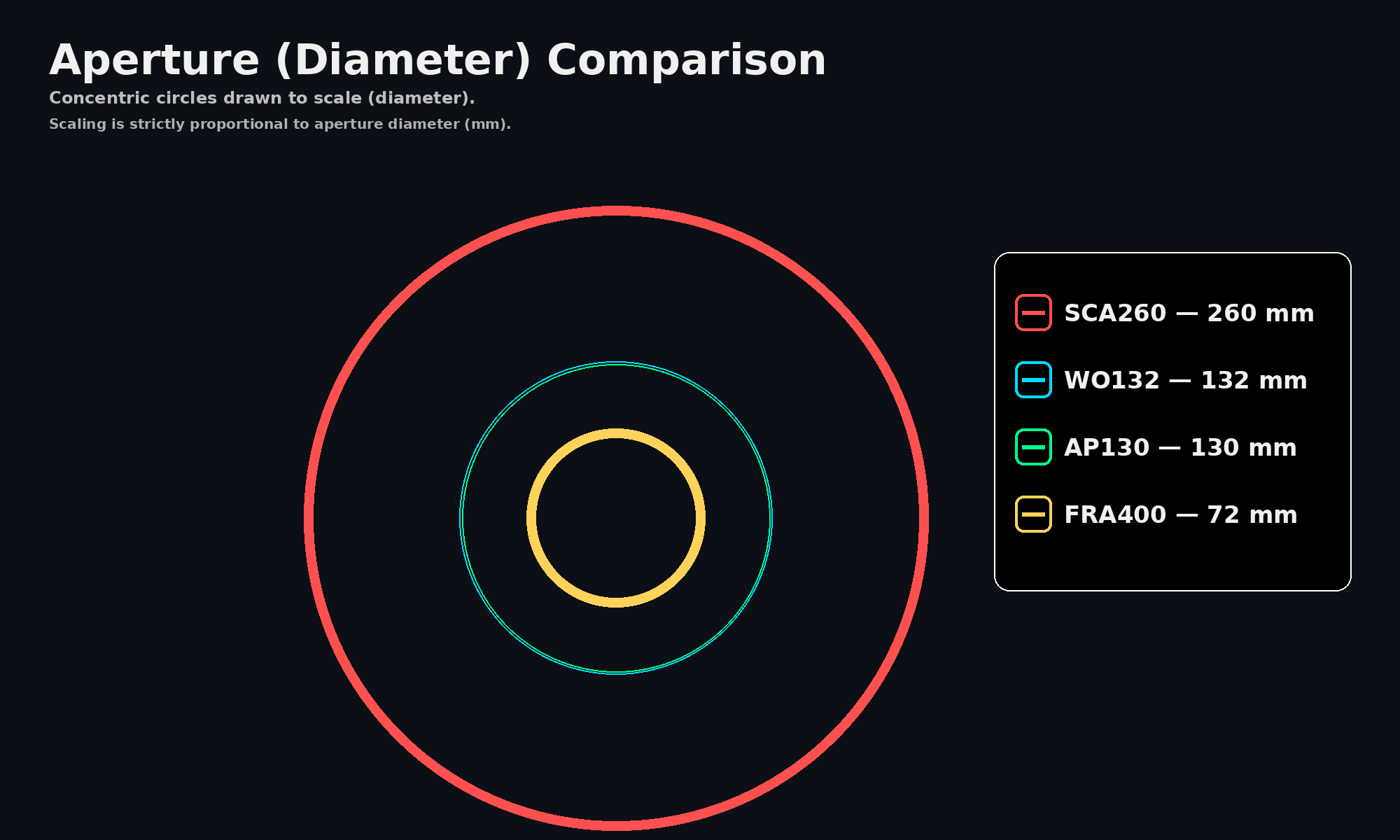

Aperture is not just a bragging metric. It drives two practical things: resolution potential (seeing-limited most nights, but still) and signal collection (especially on small, dim targets when you’re already working at long focal length).

My AP130 and WO132 platforms have obviously similar diameters, while the FRA400 is much smaller and the SCA260 is much larger.

A scaled comparison of the diameters of my scopes. Note that the AP130 and the WO132 are so close in size that they blend together in this representation.

This table is a reminder that aperture is real, but it’s not the whole story.

The SCA260 is in a different league on raw light-gathering—about 13× the capture area of the FRA400—which is exactly why it dominates the small-target and “reach” work.

The WO132 and AP130 land right next to each other in diameter (and in theoretical Dawes numbers), so the practical differentiation between those two isn’t aperture—it’s focal length, speed, and the way each system behaves in real imaging.

And the FRA400 is honest about what it is: small aperture by design, trading raw reach for wide-field composition and convenience. The Dawes column is included as a sanity check, but for deep-sky it’s mostly academic—seeing, sampling, and guiding are what decide how much of that theoretical resolution you actually get to keep.

Bottom Line: if the target is small, faint, and you want detail, the 260mm system is the one that can justify the effort. The 72mm system can’t compete there—and it’s not supposed to.

C) Focal Length (Framing and Target Selection)

This is a clean, deliberate ladder from wide to tight. There’s no awkward gap, and there’s no pointless overlap.

D) f/ratio (speed vs tolerance)

Here’s how I interpret this in practice:

The f/5–f/5.6 systems are my efficiency engines. When I’m trying to build signal quickly—especially in narrowband—those faster optics get me to a satisfying SNR in fewer nights, and they’re simply easier to justify when transparency or seeing is only “decent.”

The AP130 at f/8.35 is the outlier: it’s not competing on speed, and the numbers keep you honest about that (it can take roughly 2–3× the integration time to reach the same per-pixel depth as an f/5 system on extended targets). But it earns its place because the output has a premium refractor signature—clean stars, high contrast, and consistently well-behaved correction—so when I’m willing to pay the time penalty, the resulting images are often some of my best.

That said, the AP130 can be problematic for me, as my weather does not often provide many clear nights. If I only get one clear night, the capture from my AP130 will be well behind that of my other platforms!

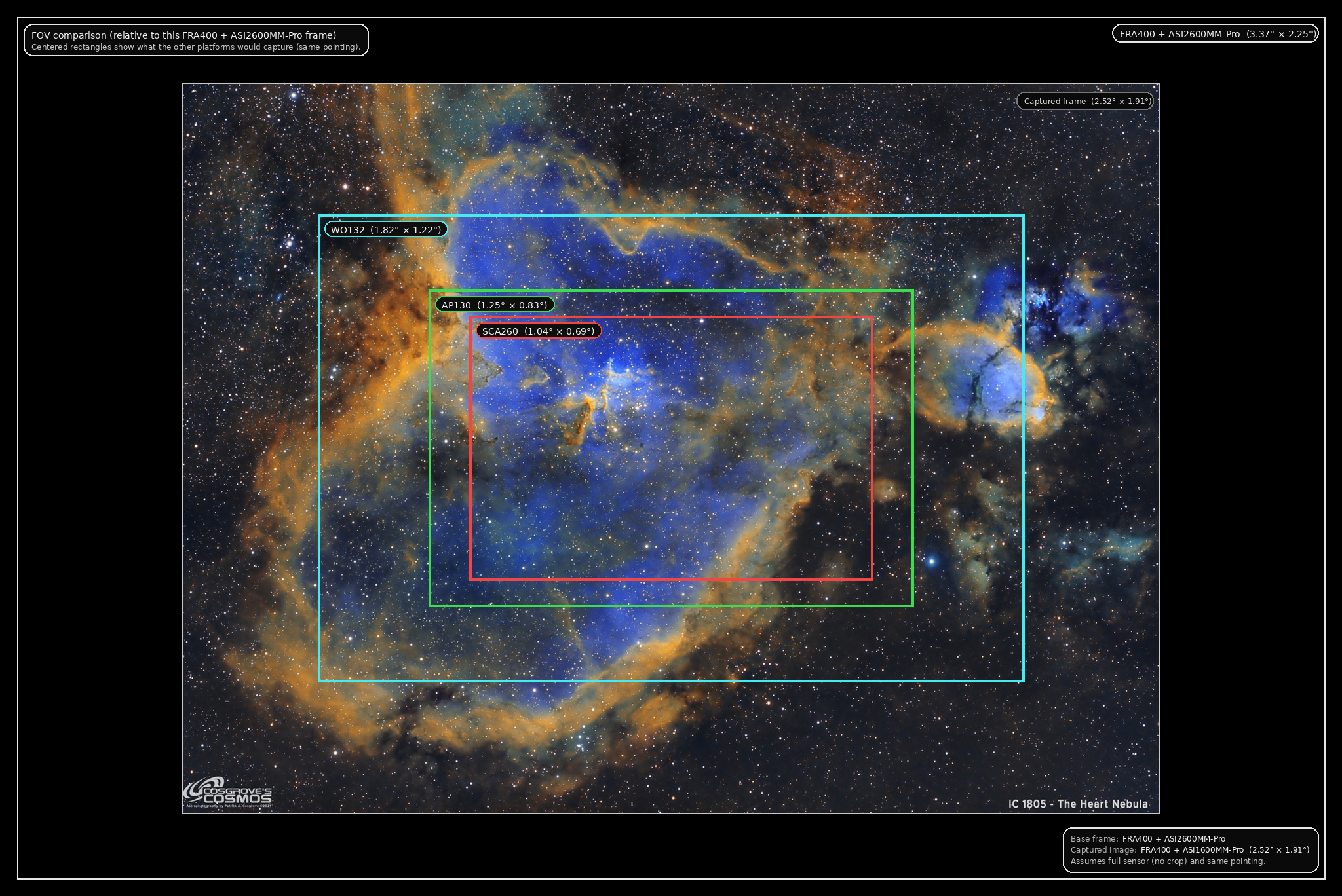

E) Field of view and image scale (what the camera actually “sees”)

If you understand one thing about this portfolio, it should be this: image scale is where the tolerance regime changes. The farther you move toward tight sampling, the more every mechanical and optical detail gets amplified.

Using the defined sensors and pixel sizes:

This image was taken with the FRA400 platform using the ASI1600MM-pro camera. However, this platform has just been upgraded to the ASI2600MM-Pro Camera. The larger sensor captures a large FOV which is now represented by the larger black square.

Here’s how I interpret these charts in the real world—where framing drives both target selection and Image framing.

These charts are where the portfolio stops being “four scopes” and starts being a deliberate coverage strategy.

The SCA260 isn’t “a little tighter” than the refractors—it’s in a different framing class, and that’s exactly why it’s my small-target / galaxy tool when I want reach and a composition that feels intentional.

The AP130 sits one rung down from that: it still frames on the tight side, but it brings classic premium refractor behavior—clean rendering, strong contrast, and a very “high confidence” feel session to session. It’s the scope I reach for when I want detail without reflector fuss.

The WO132 is the true generalist in the lineup: it lives in the sweet spot where a lot of nebulae and medium-sized galaxies fit naturally, with enough scale to feel detailed without being constantly constrained by framing.

And the FRA400 is the big-sky platform—large structures, full-region context, and fast, forgiving composition work,

F) Camera capability (sensor class and what it implies)

Next is the deliberate standardization choice: I’ve kept three platforms in the same APS-C mono camera class, the ASI2600MM-Pro, so I’m not relearning calibration behavior and processing cadence every time I swap focal length.

The last platform to be upgraded was the FRA400. Until very recently, this platform was using the ASI1600MM-Pro.

Now that all platforms are using the same camera, we can explore the specs of this camera and show how they have improved from the previous ASI1600MM-Pro model.

This chart captures why I treat these two cameras as different generations, not minor variants.

The ASI2600MM-Pro is the baseline I’ve standardized on because it gives me more of everything that matters in deep-sky work: more pixels across the frame (real resolution headroom), much more full-well capacity (better tolerance for bright cores and star control), and a more modern readout / dynamic range feel that holds up when I start pushing processing. Add in the higher QE and the “zero amp-glow” behavior, and it’s simply a cleaner, more efficient imaging engine per hour—especially on nights that are decent but not perfect.

The ASI1600MM-Pro can still deliver strong results and has earned its place, but it’s clearly built on older architecture: less full-well headroom, lower resolution, and greater reliance on calibration discipline to keep everything tidy. That’s why three platforms live on the 2600 class now, and why the 1600 is a transition platform in this lineup rather than the long-term standard. Another problem I have seen with the ASI1600MM-Pro is micro-lensing artifacts around bright stars. This can really mess up an image, and the artifacts are hard to correct for in processing.

While I have gotten good images with the 1600 series camera, I am very happy to have upgraded to a 2600 series camera.

Once the sensor and pixel scale are set, the next practical question is: can I control framing and repeat it—without adding mechanical risk?

G) Camera Rotators

Rotation is a workflow decision, not a badge of sophistication. On some platforms, it buys efficiency and repeatability; on the SCA260, I intentionally trade that convenience for stiffness and fewer failure modes.

Rotators are part of the imaging train, not the mount, and I treat them like a framing and repeatability tool—not a luxury accessory.

When you’re building a portfolio that spans wide nebula complexes through tight galaxy work, the ability to set orientation deliberately (and return to it later) is a real productivity gain. But rotators also add a mechanical interface to the camera stack, so they’re not “free.”

On the platforms where framing flexibility matters most, I use them. On the platform where mechanical simplicity matters most, I don’t.

On the FRA400, WO132, and AP130, a rotator pays for itself: it makes composition intentional, it makes multi-night projects repeatable without guesswork, and enables flat frames to be collected when needed.

The SCA260 is the exception by design.

That platform runs an OAG and lives in the tightest tolerance regime of the four systems. Every extra joint in the train is another opportunity for tilt, sag, cable torque, or a spacing surprise—exactly the kind of friction that shows up as star shape problems at 1300mm.

And for galaxy work, rotation usually isn’t the constraint; galaxies tend to sit near the center of the field, and orientation is rarely the reason a project succeeds or fails. So I kept the SCA260 camera side intentionally simple: fewer interfaces, fewer variables, more stability.

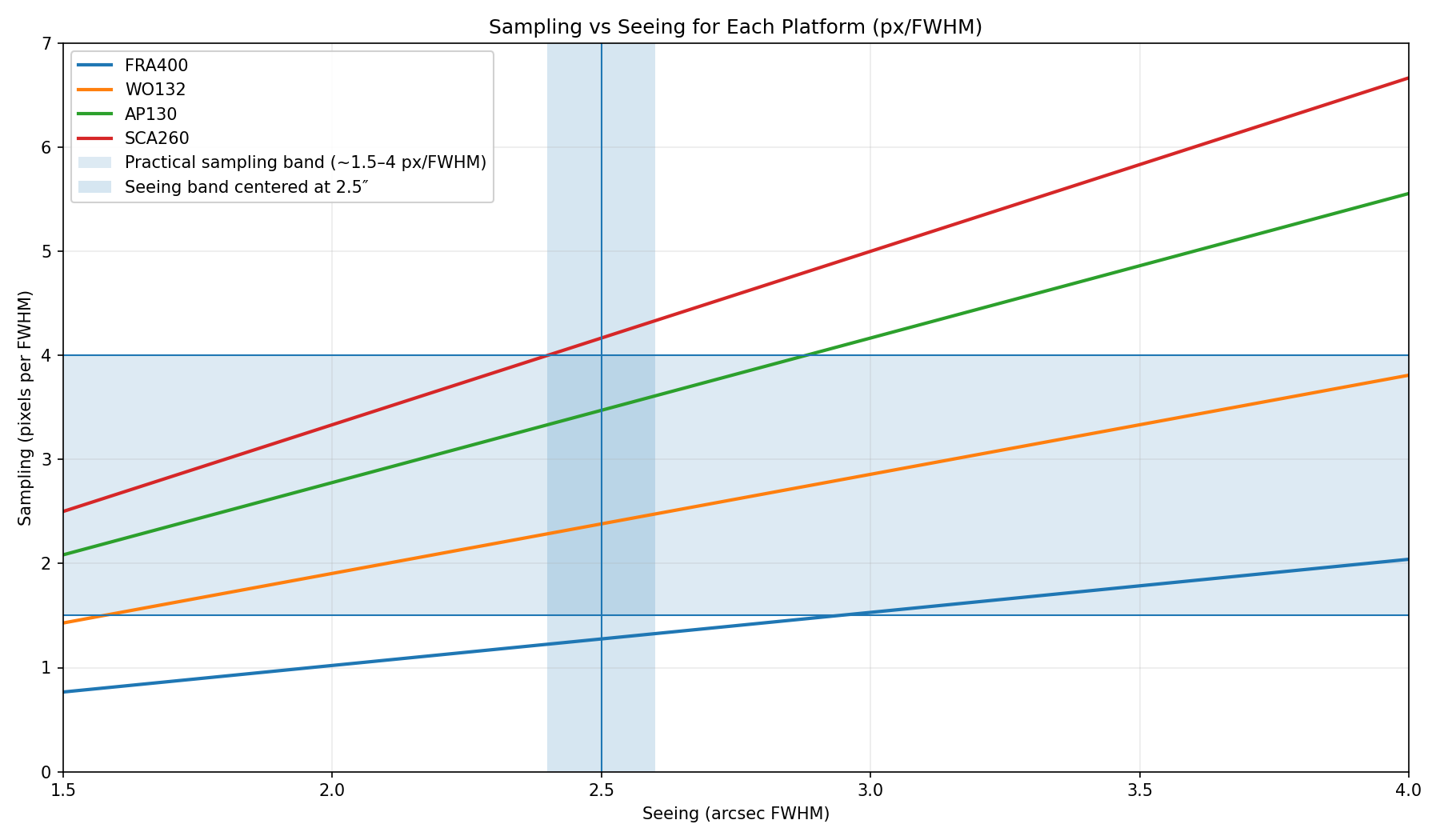

H) Sampling characteristics under a common seeing assumption

This is where the numbers keep you honest. Using 2.5″ seeing:

Blunt Conclusion:

This chart is the reality check I actually use.

The FRA400 lives on the wide-field side of the trade—at typical seeing, it’s simply not sampling fine structure, so it won’t magically turn mediocre nights into tight star profiles. What it will do is deliver clean, attractive wide-field compositions with a lot of context, and that’s exactly why it’s in the lineup—but it is not a “resolution platform.”

At the other end, the SCA260 is absolutely resolution-ready on paper, but my atmosphere often won’t let me cash the full check; most nights I’m still seeing-limited, not optics-limited. It still wins when I’m framing small galaxies and tight groups, but the right mindset is: the scope can do it, the sky has to cooperate.

It also acts as another reason to upgrade my FRA400 platform with a 2600 camera!

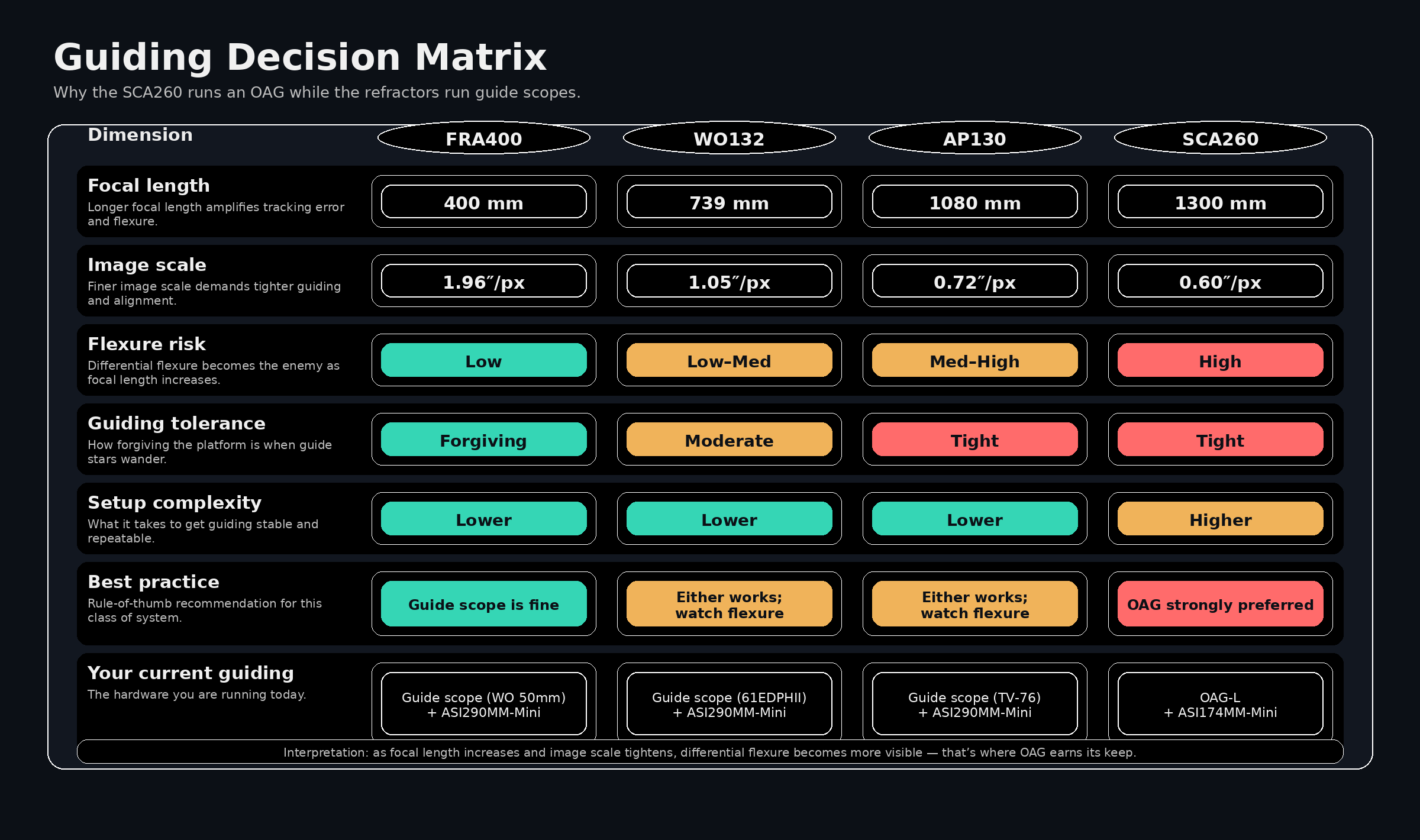

I) Guiding setups and what they say about intent

Guiding is the unglamorous part of deep-sky imaging that decides whether your optics ever get a chance to shine.

The mount can be “good,” the scope can be “excellent,” and the sky can be “decent”—and you can still throw away resolution if the guide solution is mismatched to the platform.

The core issue is simple: as focal length goes up and image scale tightens, everything gets amplified—tracking error, wind, cable tug, and especially differential flexure.

That’s why guiding isn’t a one-size-fits-all choice in this portfolio.

Guide scopes are fast, convenient, and often perfectly adequate on wide and mid focal lengths, but at the long end, you’re living in a world where small mechanical errors become visible in the stars. That’s where an OAG (Off-Axis Guiding) stops being “extra complexity” and becomes the most reliable way to keep the imaging train honest.

Guide cameras are part of the guiding system, not an accessory.

Once you decide how you’re guiding (guide scope vs. OAG), the next question is what kind of guide camera makes that method easier to live with.

A guide scope usually gives you a generous field and plenty of bright stars, so the camera can prioritize low noise and fast, clean centroiding.

An OAG is the opposite: the pick-off prism sees a much smaller slice of sky, star availability can be hit-or-miss, and you often have to guide on dimmer stars by necessity. That’s why I don’t treat guide cameras as interchangeable — the guiding modality drives the requirements, and those requirements can justify different cameras even within the same overall imaging portfolio.

Guiding is where the architecture matters. The wide-field rigs can use guide scopes without drama; the long-focal-length platform benefits from OAG behavior because it keeps the guide signal inside the same flexure regime as the imaging train.

I run two guide cameras because the job is fundamentally different depending on whether I’m guiding with a guide scope or an OAG.

With a guide scope, I’m star-rich and field-rich, so the ASI290MM Mini’s low read noise and fine pixels are a great match — it locks easily, stays stable, and doesn’t need hero exposures to find a star.

An OAG is the opposite: fewer and dimmer stars. That’s where the ASI174MM Mini earns its keep. The much larger sensor area and 5.86 µm pixels make it dramatically more forgiving about guide-star availability, especially when you’re chasing dim stars off a prism.

In practice: I use the 290 for easy, consistent guiding on the refractors; 174 for the SCA260 where star-finding and rigidity are non-negotiable.

This matrix is basically my justification for why the SCA260 runs an OAG while the refractors mostly don’t.

The FRA400 is forgiving: short focal length, wide image scale, low flexure sensitivity—so a guide scope is straightforward and the whole system stays low-drama.

The WO132 sits in the middle: still very manageable with a guide scope, but it’s the first place where I start paying attention to flexure and mechanical cleanliness because it can show up if I’m sloppy.

The AP130 is tighter again—still “refractor predictable,” but now I’m operating in a regime where guiding tolerance is less forgiving, and the penalty for flexure is real, even if the optics themselves are easy to live with.

Then there’s the SCA260: longest focal length, tightest image scale, and the highest sensitivity to alignment and rigidity. That combination is exactly why the best-practice answer becomes blunt: OAG strongly preferred. It’s not because guide scopes can’t work at all—it’s because at this scale, the system will reveal every weakness upstream, and the OAG is the most direct way to remove differential flexure from the equation.

What this reveals about the design choices:

Off-axis guiding on the SCA260 is the serious choice for long focal length: it removes differential flexure as a major variable and keeps stars tighter when the system is behaving.

Guide scopes on the three refractor platforms are a pragmatic trade: simpler setup, easier troubleshooting, and generally sufficient at their image scales—especially the widefield FRA400, where the tolerance is inherently higher.

The Key Takeaways

This portfolio is not four versions of the same idea. It’s a deliberate coverage strategy:

Optical design diversity (refractor + Petzval-like astrograph + super-Cassegrain)

Focal length ladder (400 → 739 → 1080 → 1300mm)

Camera standardization where possible (three systems on the same APS-C mono camera class )

Guiding choices that match the tolerance regime (OAG where you need it; guide scopes where you don’t)

Refractor + Petzval-style astrograph + super-Cassegrain — different tools for different problems, not redundant hardware.

A clean ladder: wide → mid → reach → tight framing.

APS-C mono across three rigs—consistent math, calibration, processing.

OAG where you need it; guide scopes where you don’t — pick the architecture that fits the flexure risk and image scale.

The next table summarized how I utilize this set of scopes.

Each clear night, I put all four scopes to work on a set of targets. On those wonderful long nights of Fall, there may even be two sets of targets. A primary set and a secondary set that I go after once the primary target has set.

So when clear, moonless nights are anticipated, you will see me go through a flurry of target-selection activities.

As I pick the targets I want to pursue, I have to decide which telescope platform is best suited for each target.

I tend to use the criteria above because they are logical and make sense. But not always. Sometimes I have more than one wide target - one will go to the FRA400, and then I decide where to place the second. It also means I will spend more time on composition and framing, as I may have to use a scope that is not ideal for image scale or field of view.

So mapping targets to scope isn't always straightforward, but I try to be smart about it.

Having these scopes in my observatory gives me many options when I hunt for targets, and that is a very good thing!

Closing

Each clear night, I try to put all four scopes to work on a set of targets. On those wonderful long nights of Fall, there may even be two sets — a primary plan, and then a secondary plan once the first target(s) have set.

So when a clear, moonless night is coming, you’ll usually see me in a flurry of target selection and re-selection. I’m not just choosing what I want to image—I’m also choosing which platform gets which target.

Most of the time, the mapping is logical: target size and structure drive focal length; faintness and detail drive “reach.” But it isn’t always clean. Some nights I have more than one wide-field target, and the FRA400 can only do one of them. Some nights, the best target in the sky doesn’t land neatly on the “perfect” scope, so I compromise and spend more effort on framing and composition to make the most of what I have available.

That’s the real point of this observatory portfolio:

I’m not trying to own four telescopes. I’m trying to own four capabilities.

Wide context. Mid-scale flexibility. Refractor detail. Small-target reach.

And when the sky finally cooperates — which is never as often as we’d like — having those options ready to go means I can spend the night collecting photons instead of wishing I had brought a different tool.

Clear nights are rare. When I get one, I want zero regrets.

Future Upgrades (Planned)

With this set of platforms, I have achieved the platform set I wanted, spanning a range of useful focal lengths.

That said, there are some changes I would like to make.

FRA400 camera standardization

This one has already happened! I have updated this document to reflect that.

The “Slow” AP130

I love this scope and have taken some really nice images with it. But it is SLOW. This isn't a big deal if you have a string of clear nights. You can just increase your integration time. But my weather is rarely so cooperative, and I have to make the best of the few clear nights that I can. To this end, I have been contemplating a change to a faser scope. A good friend has an AP155 for sale at a very good price. This is essentially the same scope, but with a much larger diameter.

I could keep the same focal length and image scale and move to a faster f/7 system. This would offer a nice improvement.

That scope also comes with a 0.75X reducer, which would give me a focal length of. about 810mm and an f/ratio of 5.3. This would have some overlap with the WO132 platform. Should I go this way? It would give me two fast scopes in this class, allowing me to better take advantage of the weather here. It also gives me an interesting opportunity: I could set the same target for both the AP155 and the WO132 and combine the datasets. This would allow me to double my integration time on target for each night!

Auto covers

I am very interested in obtaining a powered telescope flap with a flat-field light source for each instrument.

This would allow me to better automate the start and stop of telescope sessions remotely from the house and to automate the gathering of Flat calibration files.

Note: I just installed the Wanderer Astro WandererCover V4-EC 125mm on the FRA400 platform, and I will be testing that. If I am happy with it, I will install these on the other platforms. Initial impressions of this product are very positive so far.

If/when those changes happen, I’ll document them as a new hardware revision (so the page remains a faithful snapshot of what I was actually running at the time).