What Kind of Astrophotographer Am I? What Kind Are You?

February 21, 2026

Introduction

Astrophotography is not a specific thing, and it is not done in a specific way. It is actually a very rich field of target types, camera types, and various capture and processing modalities that are often specific to the target you are after and to how you like to do it.

I thought I would share with you who I am as an astrophotographer.

Then I would ask who you are as an astrophotographer as well.

Astro Profile Compass

● interpretable signature

Profile

fast scan → deeper dive below

Cosgrove’s Cosmos

Astrophotography

Profile Characterization

—

This is one way to summarize where I am as an astrophotographer. It's sort of like a fingerprint, if you will.

Let me expand on each dimension of this fingerprint.

This/Not That

Area of Focus

This: Deep-sky targets—galaxies, nebulae, and clusters.

Not that: Milky Way landscapes, wide starfields, planetary or solar work, or even casual comet imaging as my main lane.

Why: I’ve always been fascinated by faint things that are far, far away. It still feels like magic to capture a thin stream of photons that has traveled thousands—or even millions—of years to reach my sensor. Deep sky rewards patience and methodical consistency, and it’s where I most enjoy the blend of planning, execution, long-form signal gathering, and image processing. I may expand into solar system imaging someday, but for now, deep sky is my exclusive focus.

Sky Quality

This: Bortle 5 backyard skies.

We moved recently, specifically to find land where I could build an observatory. We could have pushed farther out for darker skies, but life is a series of compromises. We also valued living in a traditional neighborhood and maintaining reasonable access to local resources. Moving farther south would have added 40 minutes to an hour to the round-trip to Rochester—and as we get older, that matters. So this is where I image from, and I work within its constraints. The upside is that it forces discipline: gradient management, calibration, and workflows that function in real-world conditions.

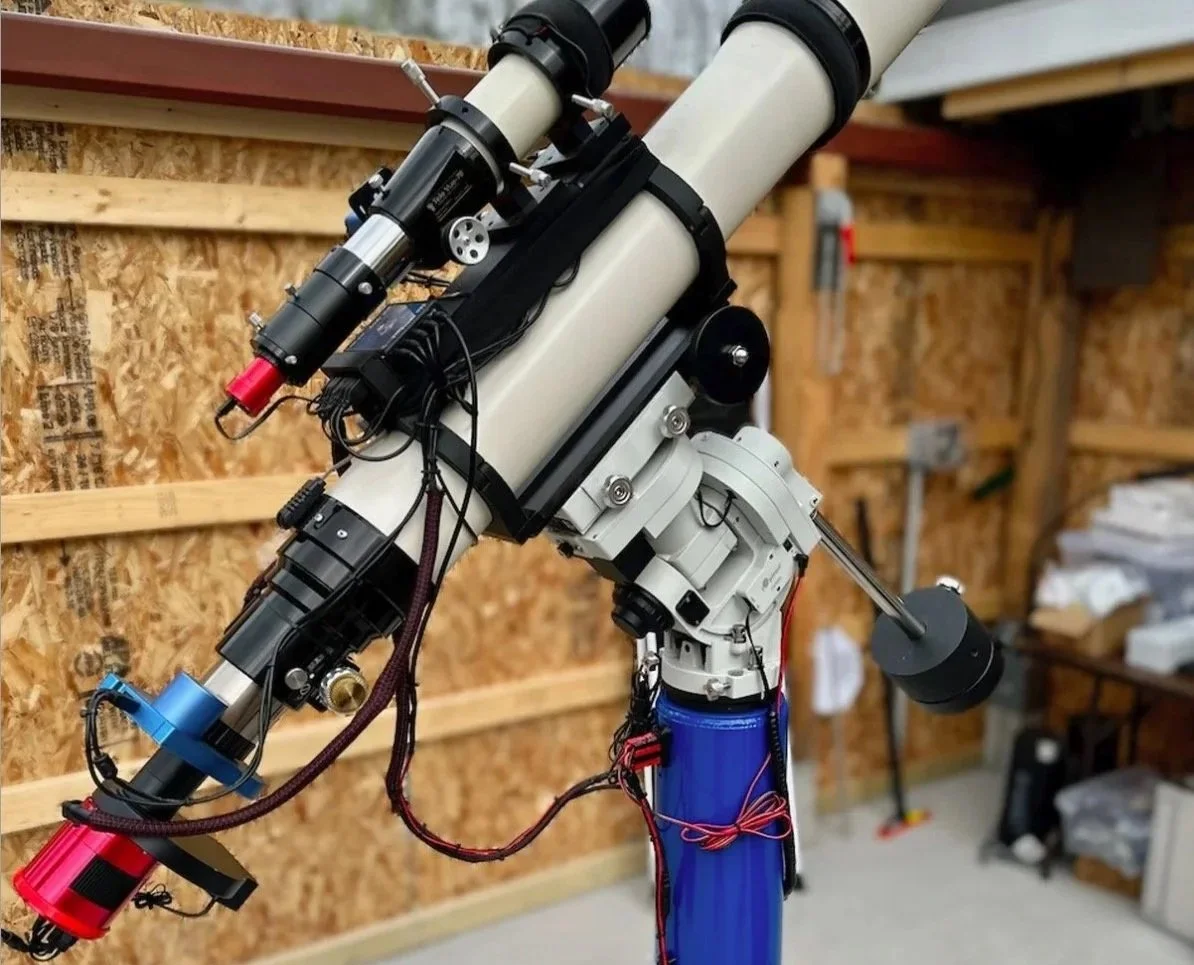

Mount

This: I run GOTO Computerized mounts on four piers in my observatory. These are necessary for integrating faint photons. A GoTo equatorial mount with automated pointing and tracking.

Not that: Tripod-only shooting or a simple tracker workflow as the default. This would prevent me from playing the Deep Sky games I am interested in.

Why: Deep-sky work lives or dies on tracking, repeatability, and the ability to return to targets reliably across multiple nights. The mount is the foundation of an imaging platform. Some people buy premium, top-tier mounts—I envy that route—but I’ve tended to choose lower-cost, reliable mid-tier mounts that have performed well for me.

Control Hardware

This: A headless micro-PC for each telescope

Not that: Running the session from a laptop next to the mount, or relying on a phone-first appliance workflow.

Why: I’m comfortable with PCs and networked systems, so capturing software on a computer always felt natural to me. For years, I used refurbished business laptops (back when they were cheap), but once I built the observatory, it made more sense to move to a headless micro-PC at each pier. I connect to them from the observatory computer or—more often—from my “Astro Man Cave” back in the house. A dedicated control computer keeps the system consistent, reduces friction, and supports a full software stack without compromise. It also gives me the widest set of options for control software.

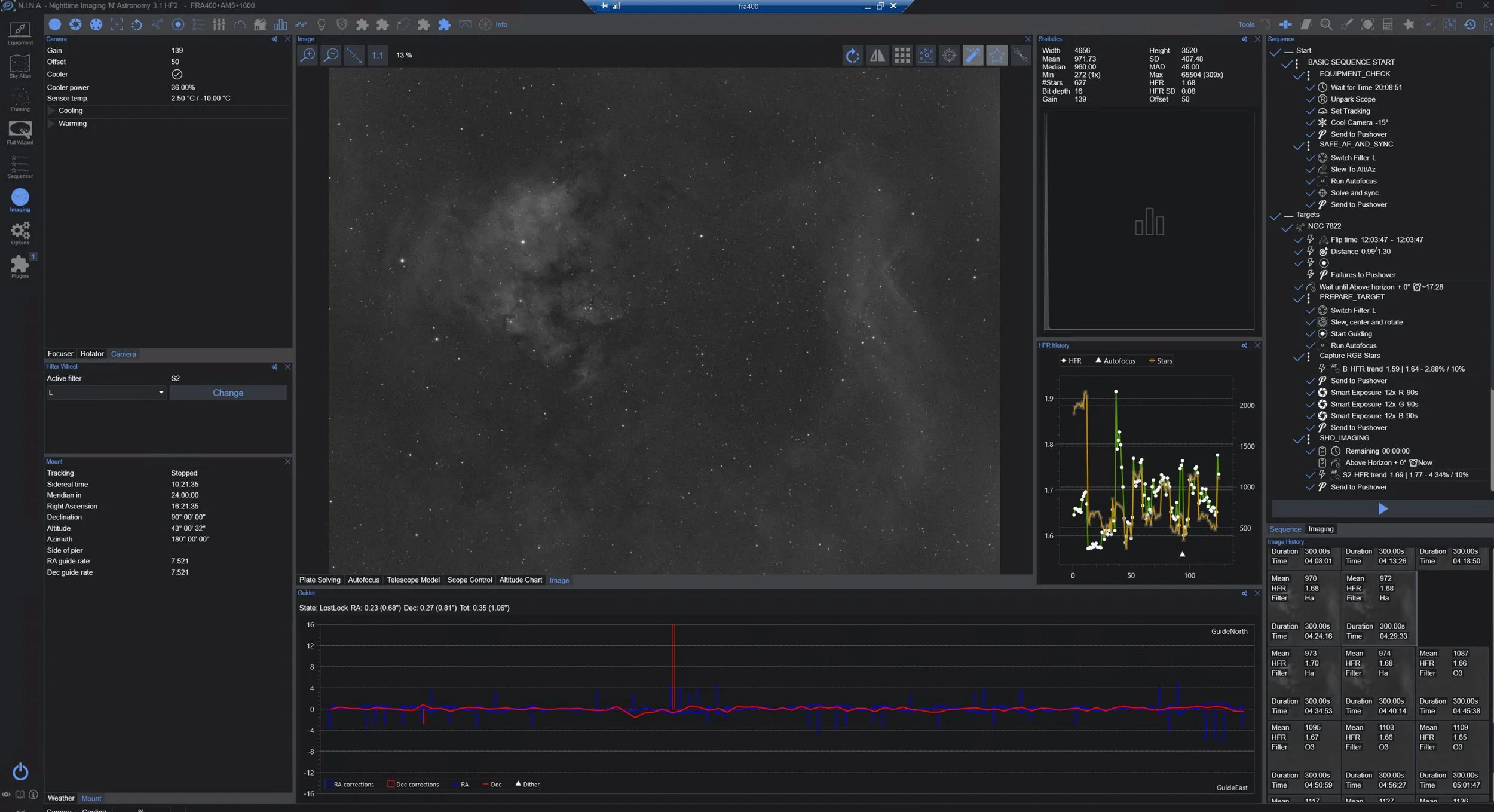

Automation Software

This: PC-based capture and guiding with NINA + PHD2.

Not that: An appliance controller (ASIAIR / Stellarmate), or other PC suites, as my primary approach.

Why: I want depth, flexibility, and repeatability. The goal isn’t “better software”—it’s a workflow architecture that matches how I run sessions and manage multiple rigs. I started with Sequence Generator Pro years ago. It was premium software, but my license covered three seats, and I needed four when I moved into the observatory. That pushed me to try NINA, and I ended up loving it. I converted all my systems, and it dramatically improved my automation. PHD2 for guiding was an easy choice because it’s proven, widely supported, and integrates cleanly with how I work.

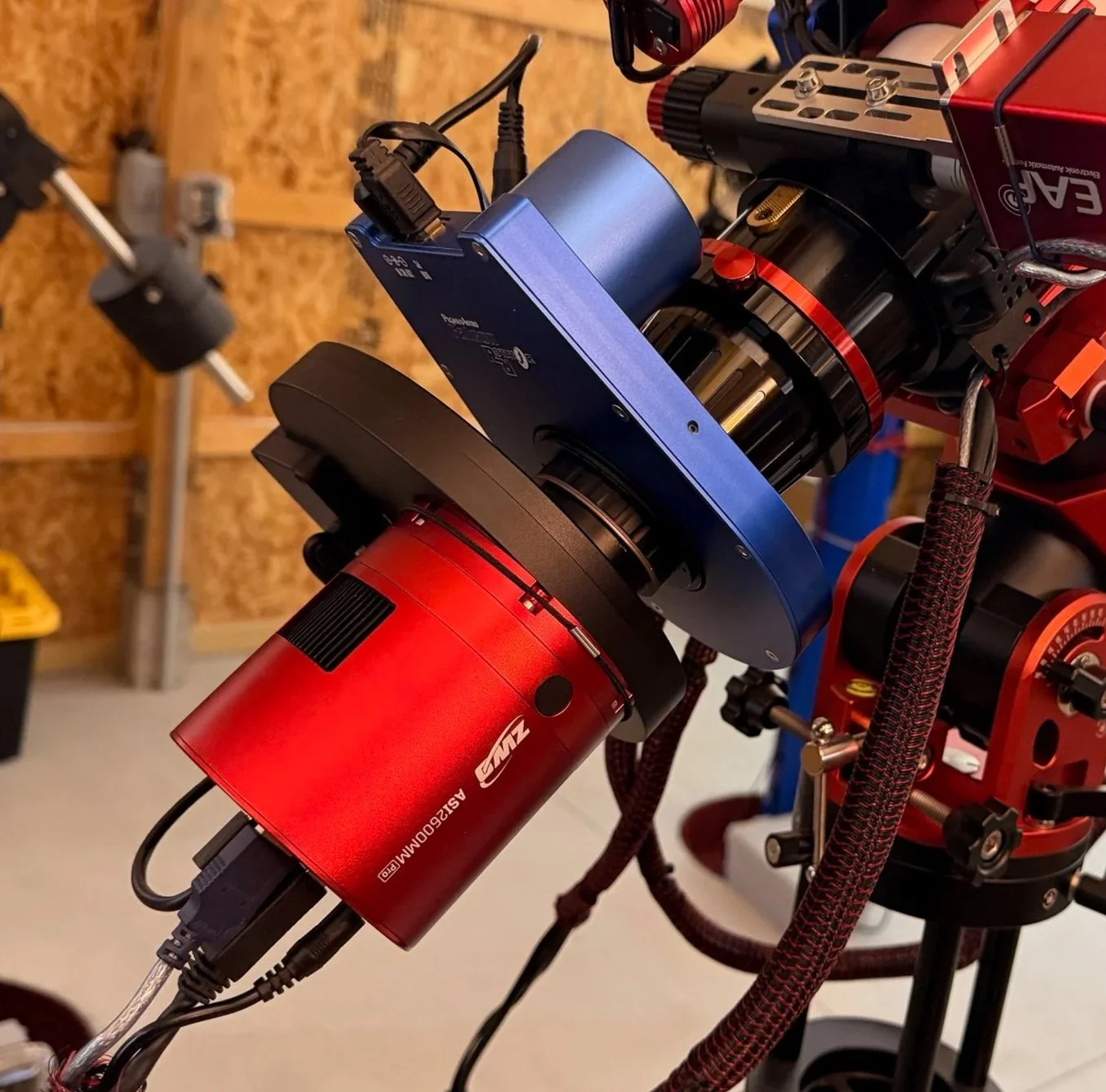

Camera System

This: Dedicated cooled mono astro cameras + filters.

Not that: Phones, DSLR/mirrorless-only imaging, or one-shot color as my primary system.

Why: Mono + filters increases complexity, but it provides excellent control over signal, bandpass, and the balance between stars and nebulosity—especially under imperfect skies. It also gives me the flexibility to shoot LRGB broadband, SHO and HOO narrowband, and multispectral blends like HaLRGB and “SHO + RGB stars.”

Facility

I have this: A permanent observatory with four piers.

Not that: A nightly setup/takedown routine (even with a fixed pier), or a single-rig-only observatory as the defining setup.

Why: Permanent infrastructure shifts effort away from gear assembly and toward data collection. It improves consistency, reduces mistakes, and increases throughput on good nights. For many years I set up two to three telescope platforms in my driveway at night and tore them down in the morning. It can be done—but the convenience and reliability of an observatory has paid off exactly the way I hoped it would.

Roof

This: A Roll-off roof.

Not that: A dome (or no roof at all).

Why: Because I’ve always run multiple scopes, a roll-off roof was the natural choice. It gives every platform the same open sky when the roof is back, and it lets me protect everything quickly if the weather turns—close the roof and the session is safe.

Operating Mode

This: Remote operation from the house (backyard observatory).

Not that: Standing at the scope all night—or running primarily from a warm room inside the observatory.

Why: Remote operation improves comfort and attention. My automation is now good enough that I can nap on the sofa in my Astro Man Cave and get alerted to issues on my phone. Capturing photons while I sleep? Yes, please.

Scale

This: Multiple independent platforms—four scopes, with the ability to run more than one project efficiently.

Not that: A single “do everything” rig, or a multi-scope-on-one-mount setup as the core concept.

Why: Multiple rigs let me match targets to the right image scale and make better use of limited clear nights—especially when targets rise and set at different times. When conditions are good, I want to collect as much usable data as possible.

Composition

This: Rotators on most rigs.

Not that: “Close enough” framing, or re-framing from scratch each session.

Why: Rotators enable intentional composition and—just as important—repeatable framing. That means I can resume a project across nights and maintain consistent geometry for calibration and processing.

Calibration & Data Habits

This: Calibration planned as part of the conclusion of all sessions, including nighttime calibration for darks as needed.

Not that: Treating calibration as optional or as an afterthought.

Why: Good calibration protects your data. It’s the difference between spending your processing time extracting signal versus fighting preventable artifacts.

Narrowband Stars

This: Collecting RGB stars for narrowband images when possible.

Not that: Accepting narrowband star color as-is when it compromises the final look.

Why: It produces a more natural star field while preserving the narrowband benefits on the target—especially under light pollution. Weather doesn’t always cooperate, but most projects run over multiple nights, and I can usually dedicate at least one night to RGB star capture. It does complicate capture, calibration, and processing—but in my view it often produces a better final image.

The Tradeoffs I Accept

Every imaging style has a cost. These are the costs I’ve chosen to pay because the payoff matches what I’m trying to produce.

-

Complexity is the price of flexibility and capability. COST complexity → PAYOFF options

My rigs are optimized for flexibility and performance, but running multiple platforms increases complexity. Planning, setup, monitoring, and calibration all become more demanding—and there are simply more things that can go wrong. Automation reduces friction, but it doesn’t eliminate responsibility. I accept the complexity because it gives me the options I want.

-

Bortle 5 is a constraint I work within. COST less dark skies, gradients → PAYOFF convenient living

Gradients and skyglow are part of my reality, so calibration discipline and processing discipline are not optional.

-

Mono + filters means more overhead. COST workload → PAYOFF control + flexibility

More filters means more data types, more calibration, and more work organizing and processing it all. I take on that overhead because it gives me the control and flexibility I want—especially under imperfect skies.

-

Remote operation requires trust—and verification. COST design → PAYOFF comfort

It’s comfortable, but it forces you to build in monitoring, safety behaviors, and failure handling. You can’t “set it and forget it.” You have to design the system so it fails safely.

-

More rigs means more maintenance. COST upkeep → PAYOFF throughput

Four platforms can be incredibly productive, but they multiply cabling, software, firmware, and the steady stream of “small problems” that need attention.

-

Repeatability beats spontaneity. COST spontaneity → PAYOFF consistency

My approach favors running a system well over improvising a new setup every night. Consistency—on one platform and across all of them—reduces friction, reduces errors, and makes results more predictable.

A Night in My Observatory

This is what a “normal” clear night looks like for me—less romantic than people imagine, but extremely satisfying when everything settles in, and the data starts accumulating.

How a Clear Night Runs

This is what a “normal” clear night looks like for me—less romantic than people imagine, but extremely satisfying when everything settles in, and the data starts accumulating.

Target selection and assignments (daytime).

I research and select targets, then map them to the right platforms based on image scale, framing, and what’s available that night. This happens during the day. Once targets are chosen, I determine the exact framing and build a custom sequence profile for each one—usually from my “Astro Man Cave.”

Bring systems online (while it’s still light).

I open the roof and start the systems early—plenty of time for everything to cool down and stabilize. Each telescope is powered up, and the control software stack is brought online. Power, connectivity, and dew control all start from a known state.

Automation arms and waits for conditions.

I start the NINA sequences before it’s fully dark. Cameras pull down to temperature, then sequences wait for darkness. Once ready, they run autofocus, plate-solve, sync, and then wait for targets to clear the treeline. From there, NINA centers the image, using the camera rotator to set the framing exactly where I designed it. The sequences begin collecting data.

Safety and recovery routines do their job.

The system monitors focus drift, guiding stability, and other failure modes throughout the session. These routines don’t make the night “hands off,” but they handle many of the common problems that would otherwise cost you time and data.

Monitoring, not babysitting.

I check in periodically and let automation do the heavy lifting, intervening only when something needs attention. In practice, I often sleep on the sofa in my Astro Man Cave and check on things during quick breaks. If NINA detects a real problem, it sends an alert to my phone to wake me.

End-of-night wrap (automated).

When the run is complete—or when conditions degrade—NINA finishes the sequence, warms the cameras, and returns mounts to park.

Morning shutdown (manual).

In the morning, I go out to the observatory, cap the scopes, close the roof, and lock everything up.

Calibration Strategy.

When the Moon or clouds intervene, I use those windows to capture fresh calibration frames as needed. Flats at the correct target rotation (and the associated darkflats) are always collected. Darks are collected when needed. I prefer capturing calibration at night so it isn’t influenced by potential light leaks.

A quick data sanity check.

Most nights, I review the subs to confirm that the data looks good. Before I call it done, I spot-check stars, guiding, gradients, and overall quality.

The short version: I’m trying to turn clear nights into dependable data production—so the real work is designing a system that runs consistently.

What Kind of Astrophotographer Are You?

Create your own profile if you like!

Build your own “spec-sheet” profile. Each spoke is a dimension. Outward on an axis means “more infrastructure/automation/scale,” not “better.” Hover/tap a node for meaning and progression.

Astro Profile Compass

● interpretable signature

Profile

fast scan → details below

Stella’s Stars

Astrophotography

Profile Characterization

—

Build Your Profile

Select one option per dimension. The compass and the summary update immediately. Use the download button to capture a clean share card (radar + all fields; no dropdown UI).